The words covered in this article are qualified and unqualified, anomaly and anomalous, irony, autonomy, and ambivalence. Previously done words that will reoccur today are unequivocal, ambiguous, culpable and viable.

In America, the legitimacy of abortion is determined by state laws. In the pro-life states, abortion is allowed only if there is unequivocal medical evidence that a woman will certainly die if her pregnancy continues. On the other hand, the pro-choice states grant their citizens a fundamental right to an abortion until a fetus is viable.

Note the ‘until’ in this sentence. The citizens of the second category of states do have a right to get an abortion, but it’s not a right that can be exercised unconditionally. It is a qualified right.

Qualified

The adjective qualified means conditional, limited, or restricted.

Qualified rights are those rights of an individual with which the state or the court may interfere in order to protect the rights of another citizen or the wider public interest. For example, freedom of speech is a qualified right; the state can restrict your right to speak what you like if your speech endangers someone’s life or privacy. The rights to life and privacy are more fundamental, more important than the right of freedom of speech.

An unqualified right, on the other hand, is a right that cannot be balanced against the needs of other individuals or against any general public interest. For example, to recognize the right to life and the right not to be subjected to torture as unqualified rights is to say that there are absolutely no circumstances under which the state is justified in killing or torturing someone.

The right to abortion, even in those states of America that do grant this right, is a qualified right. Once the fetus becomes viable, it is regarded as independent human life, and in a state where the right to life is an unqualified right, the right of the viable fetus to live must prevail over the wish of the mother to terminate the pregnancy.

In 1973, when the Supreme Court decided the Roe v. Wade case and granted a fundamental right to abortion till the fetus became viable, the doctors believed that fetuses became capable of surviving outside the womb only around the 28th week of pregnancy. Therefore, after this point, states could reasonably restrict women’s access to abortion. However, now, with new medical techniques such as sophisticated incubators, there is a debate if the threshold of fetal viability should not be brought closer to 22 weeks.

Then, there are people who think that the benchmark that decides the legal personhood of a fetus should not be viability but presence of a heartbeat, because only living beings have heartbeats; once a fetus develops a heartbeat, it should be deemed to be living. It is interesting to note that a fetal heartbeat can be detected after just six weeks of pregnancy, at which stage many women do not even know yet that they are expecting.

Before we proceed, it will be useful to summarize the several different ideas we have encountered since yesterday about when human life begins:

- The pro-lifers declare that life begins right at the moment of conception.

- The pro-choice advocates believe that life begins at the moment of birth (and therefore, before birth, the pregnant woman’s right to choose whether to continue her pregnancy is weightier than the right of a non-living fetus to continue to grow).

- The 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision deemed a fetus to be living once it reached viability.

- Some people today believe that the non-living tissue growing in a woman’s womb becomes a living being when it develops a heartbeat.

As per the pro-lifers, the only legitimate grounds for an abortion are a life-endangering health risk to the mother or a serious anomaly in the fetus that would cause either a stillbirth or death soon after birth.

Anomaly

The noun anomaly means, in this context, an abnormality. In other contexts, it could also mean an abnormal thing.

The adjective form of the word is anomalous, which means abnormal.

Mnemonic: Write the word as ‘a-no(r)mal-ous’ => ‘not normal’

The pro-choice advocates point out the irony that though the pro-lifers seem to be so concerned about the human rights of an unborn fetus, they seem to be strangely unconcerned about the human rights of the woman who is carrying that fetus.

Irony

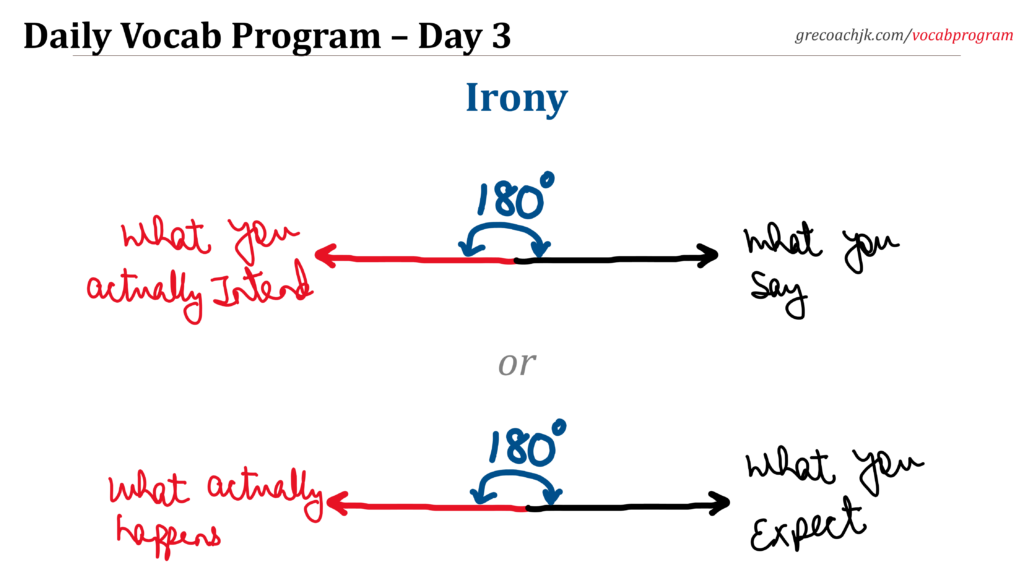

An irony is:

- a style of speech or writing in which what you say is the opposite of what you truly mean, or

- a situation in which the result of an action is the opposite of what was intended or expected

What is ironical about the stance of the pro-lifers? Let’s see. What they say is that they are very concerned about human life and human rights. However, what they actually intend to do is to take away the right of the female half of human population to make a crucial life-decision. What they intend, therefore, seems to be 180-degree opposite to what they say. Such a contrast is called an irony.

Here is another example of irony:

The USA is universally regarded as one of the most advanced nations of the world, while India is still a developing country that fares poorly on most indices of gender equality and women’s empowerment. Based on this fact, which of these two countries would you expect to have a more permissive abortion law? The actual reality is the 180-degree opposite of that expectation: in 2021, India amended its Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971 to increase the gestational age of abortion from 20 to 24 weeks (in special circumstances), while in 2022 the Supreme Court of US took away the legal framework that allowed American women to get safe abortions without criminal culpability.

So, it can be considered ironic that the laws of America grant its pregnant women much lesser autonomy than do those of India.

Autonomy

Autonomy means independence, the ability to decide for yourself without being controlled by anyone else.

Origin: Greek autos, self + nomos, rule => ‘self-rule’ => ‘not ruled by anybody else’

The adjective form of this word is autonomous.

The pro-choice camp frames the issue of abortion in terms of a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body. “My body, my choice” is a popular slogan used to pushback attempts to limit a female’s bodily autonomy. These advocates ask if denying the right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy to a woman and thus forcing her to bear an unwanted child is not effectively the same as denying her equal citizenship and personhood.

As feminist writer Ellen Willis wrote in a 1985 essay,

“The central question in the abortion debate is not whether a fetus is a person, but whether a woman is. . . As I see it, the key question is “Can it be moral, under any circumstances, to make a woman bear a child against her will?”

Though the heated debate between the pro-choice and the pro-life camps has been going on for decades, no side has won yet. Most Americans remain deeply ambivalent about abortion.

Ambivalence

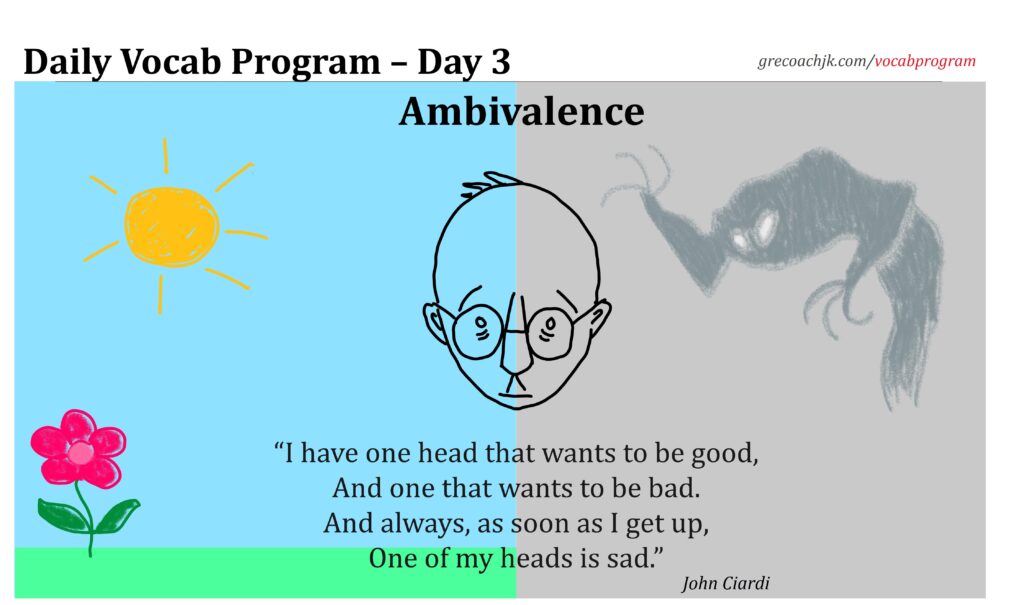

Ambivalence is the state of being in two minds about something. If one part of you wants to do something but another does not want to do it, you are ambivalent. If you have mixed feelings towards something, you are ambivalent. If you have to make a ‘Pros’ and ‘Cons’ balance sheet to arrive at a decision, you are ambivalent.

Origin: Latin ambi-, both, + valentia, strength => ‘both sides of the argument (do it/ don’t do it) are equally strong.’

(Note: you have encountered Latin ambi- once before, in the Day 1 word ambiguous)

The Latin word valentia has a Sanskrit cousin – bal – which sounds similar and means the same. Some Hindi words from the root bal are balwaan (strong), nirbal (weak, without strength or power), and abla (weak, without strength or power).

Linda Bird Francke, an award-winning journalist and a mother of three, wrote an Op-Ed page article in The New York Times in 1976, titled There Just Wasn’t Room in Our Lives Now for Another Baby. She had just taken a full-time job and her husband was planning a career change when her fourth pregnancy happened. The couple firmly chose abortion but, right before and after the procedure, they were surprised by the ambivalence that hit them. Meaning, they started off as very sure about this decision, but when the time came, they experienced conflicting emotions – while one part of them wanted to go ahead, the other did not.

Here are some excerpts from her article:

“When my name was called, my body felt so heavy the nurse had to help me into the examining room. I waited for my husband to burst through the door and yell ‘Stop,’ but of course he didn’t. . .

Finally, then, it was time for me to leave…. My husband was slumped in the waiting room, clutching a single yellow rose wrapped in a wet paper towel and stuffed into a Baggie.

We didn’t talk all the way home….

My husband and I are back to planning our summer vacation now and his career switch.

It certainly does make more sense not to be having a baby right now—we say that to each other all the time. But I have this ghost now. A very little ghost that only appears when I’m seeing something beautiful, like the full moon on the ocean last weekend. And the baby waves at me. And I wave at the baby. ‘Of course, we have room,’ I cry to the ghost. ‘Of course, we do.’”

So you now have a fair idea of how the fierce debates around abortion are closely related to the ambiguity about what ‘life’ means and when it begins. Tomorrow, you will learn about the complications that result from the ambiguity about the meaning of ‘death.’

Before we call it a day, here are some more usage examples for ambivalence:

The poem in the image, written by John Ciardi, is about a man who is ambivalent towards good and evil. His self is divided – one part wants to be good, and the other wants to be bad. Both Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde live in him, as they do in most of us.

Ambivalence within a society about an issue means that the society as a whole is not sure of what stand to take on that issue. For example, public attitudes toward humility are marked by ambivalence. We are taught to not be proud of our achievements or to brag about them, and yet our culture rewards self-promotion far more than humility.