The words covered in this article are analogy and analogous, explicit and explication, implicit, imply and implication, metaphor, and vivid. Previously done words that will reoccur today are perception and perceive, connotation, and unequivocally.

Analogy

An analogy is a similarity between two distinct things, based on the perception of a shared property or a shared relation.

That is, if two things are actually quite different from one another but we sense them to be similar in some way, then such a similarity is called an analogy. This word comes from the Greek word analogia, a mathematical term that means ‘proportion (equality of ratios).’

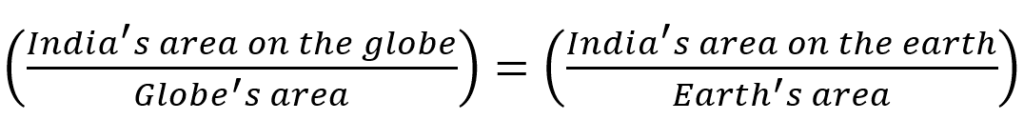

Let’s understand analogies by considering a globe and the earth.

These are quite distinct objects that are, nevertheless, similar in one way – they are both round balls. We use this shared property to make the smaller round ball (the globe) a useful model of the bigger round ball (the earth). The area occupied by a country on the globe is in the same proportion as the area occupied by it on the earth. For example,

So, we can say that a globe is an analog of the earth. Another way to say the same thing: the globe is analogous to the earth.

Like globes, maps too are simpler models of actual geographies. A map of your city is just a paper drawing, quite a different thing physically from the city, which is made of buildings and roads and gardens. But the map is also similar to the city in that it looks just like the city would look from above. A map represents all places and distances in the same relative size as in the actual city. The ‘scale’ used by a map explicitly tells us the ratio of the on-map distance to the on-ground distance. For example, 1 centimeter on the map may represent 1 kilometer on the ground. Therefore, we say that maps are two-dimensional analogs of three-dimensional places.

Explicit

Explicit is an adjective and means clearly expressed, leaving nothing unstated.

Its adverb form is explicitly.

Some movies contain ‘sexually explicit scenes,’ which are scenes that leave nothing to the imagination; they show everything.

To explicate an idea, say the idea of individuality, means to make it clear, to explain it fully. If a novelist uses her fiction to explicate our social concerns about race, gender and class, this means that her novels explain clearly, in an easy-to-understand manner, the different points of view that people have on these issues and how those subjective beliefs interact in the society.

An explication is a full and clear explanation of the meaning of something. A dictionary often contains an explication and illustration (through examples and/or helpful diagrams) of difficult words, the specialized vocabulary of various fields, and common proverbs.

Implicit

Implicit is the opposite of explicit. The adjective implicit means unstated but understood.

When you say nothing about a misdeed, when you do not disapprove it explicitly, people may assume that you don’t really mind it or even that you implicitly approve of it.

Implication

To imply something is to say or show indirectly (implicitly, not explicitly).

Today’s movies may choose to show kissing, sex and murder explicitly, but this was not always the case. In old Bollywood (Indian Hindi film industry) movies, kissing was rarely and sex was never shown on-screen. Rather, they were implied, by showing perhaps two birds pecking at one another or a bee sitting on a flower. Presented below is a short snippet from the 1965 movie Guide. Though the camera zooms out from the couple and starts showing trees, we still have been given enough hints to understand what’s going on behind those trees.

An implication is something that is not said directly (explicitly) but can be naturally understood. When a villain in a movie says to the hero, “If I were you, I would leave the matter alone,” the implication is that the villain will not hesitate to harm the hero if needed.

Getting back to our discussion on analogies, it is commonly believed that the ability to identify and make analogies correlates with intelligence:

“. . . some people are far more sensitive to resemblances, and far more ready to point out wherein they consist, than others are. They are the wits, the poets, the inventors, the scientific men, the practical geniuses. A native talent for perceiving analogies is reckoned by [many] . . . as the leading fact in genius of every order.”

William James (1842-1910). James is said to be the ‘Father of American psychology.’

- By ‘native talent’, James means inborn talent.

- The phrase ‘leading fact in genius’ is used here to mean something that indicates a person’s genius before she has made the achievements that unequivocally prove such genius. How might we know today that a little girl who is playing with her toys in front of us is a genius and is going to make groundbreaking discoveries in science one day? According to James, the fact that this child is quite good at picking up analogies between things that we only see to be quite different might give us a clue.

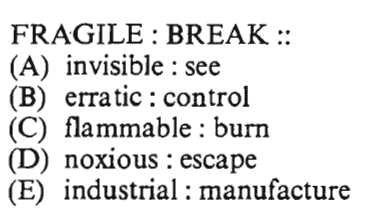

Because analogies are thought to be a leading measure of genius/intelligence, they are a part of many standardized tests. Before 2011, the GRE verbal section too used to have analogies questions. Here is one such question:

The question is: which of the five options is in an analogous relationship to the given words?

Earlier in today’s lesson, you’ve learnt that the word analogy comes from the Greek analogia, which means ‘proportion (equality of ratios).’ The above question reinforces this etymological link by using the same notation that is used to represent proportions in mathematics.

In mathematical contexts, the relationship A:B :: C:D is read in one of the following ways:

- The ratio of A to B is the same as the ratio of C to D.

- A is to B as C is to D.

For example, if a recipe demands that you put in 1 cup of rice for every 4 cups of milk, then if you put in 5 cups of rice and 20 cups of milk, you are maintaining the same ratio. You will get the same taste as promised by the recipe but five times as much amount of the cooked dessert.

In the GRE question above, the mathematical notation for proportion is used not for numbers but for words. In the context of words, the statement A:B :: C:D can be read in the following ways:

- The relation of A to B is the same as the relation of C to D.

- A is to B as C is to D.

How does fragile relate to break? A thing that can break is called fragile. So, our relationship template is:

A thing that can <2nd word> is called <1st word>.

Which of the five options follows the same template? We find that only Option C does: A thing that can burn is called flammable.

In his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson gave this example of analogy:

“Learning is to the mind as light is to the eye.”

This example can also be expressed as:

learning : mind : : light : eye.

Just as the eye cannot see without light, the mind cannot see without learning. The relationship template here might be described as:

The <2nd word> cannot see without the <1st word>.

Here then is a summary of what we have learnt about analogies so far:

We make an analogy when we say:

- This thing is like that thing, when the two things are actually quite different. An example of this was our saying that a globe is like the earth.

OR

- This relationship is like that relationship. For example, fragile : break :: flammable : burn, and learning : mind : : light : eye.

Moving onwards, an analogy that says, ‘this ABSTRACT thing is like that thing,’ is called a metaphor.

Metaphor

As an example of an abstract concept, take ‘bravery.’ When we read that someone was ‘very brave in the battlefield’, we form only a dim image in our mind of how he fought, if we form an image at all. Compare this with:

He was a lion in the battlefield.

Why is this statement an analogy? Because it says the conduct of this man in the battlefield was like the conduct of a lion in a jungle, whereas we tend to think that because a human and a lion are quite different organisms, their behavior too will be dissimilar. So, two actually different things are here said to be alike, based on one parameter.

(The man) : (the battlefield) : : (A lion) : (the jungle)

Why is this statement a metaphor? Because the perceived similarity between the man and the lion is based on an abstract quality – the confidence and the power with which he carried himself in the battlefield.

The advantage of describing this person as ‘a lion in the battlefield’ instead of merely as ‘brave’ is that the metaphorical expression is much more vivid. It brings to our mind a bright, movie-like image of how the man fought – we see him roaring in the battlefield and lording over the weaker-hearted opponents as they retreat fearfully to save their lives.

Vivid

Vivid is an adjective that means full of life, color or detail.

The Latin parent of this word is vivo- which means ‘to live.’ So, vivid means ‘lifelike’ or ‘full of life.’ Other words from this root are ‘survive’ and ‘revive,’ which means ‘to bring back to life’ (the prefix re- means ‘back’).

If you say that an old lady’s description of her childhood home was vivid, this means that she described the rooms, the furniture, the courtyard and the trees in such rich detail that you could see them in your mind’s eye; you felt that you were actually in that place!

You have earlier encountered this word in the vocab program in Sunday Read 1, in the following context:

“At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it, and at the sight of a foreigner in the streets, I would fall to weaving a network of dreams—the mountains and the forests of his distant land, with his cottage in their midst and the free and independent life, or far away wilds. Perhaps scenes of travel are conjured up before me and pass and re-pass in my imagination all the more vividly, because I lead an existence so like a vegetable that a call to travel would fall upon me like a thunder-bolt.”

An excerpt from Sunday Read 1: The Cabulliwallah, by Rabindranath Tagore

We will continue this discussion tomorrow, but before you go, here are a few more usage examples of the words you learnt today:

- When a person is called skinny, the implication is that the person is perhaps a little too thin; slender does not have a “too thin” connotation.

- Making a checklist for an important process is a good idea, because it makes the necessary steps explicit. This frees us from the mental burden of remembering a huge list of to-dos. It also reduces the risk that we will forget to do a critical task and offers us a way to verify that we have indeed done all the things we were supposed to do.

- We often tell ourselves that a technology itself doesn’t matter. It’s how we use it that is important. The implication, comforting in its arrogance, is that we are in control – the technology is just a tool, inert until we pick it up and inert again once we set it aside.

- Thoughts and emotions are said to be implicit if we are unaware of them. People may be biased against a person or a group of people without knowing that they are so biased. Such prejudice is known as implicit bias. For example, a manager who explicitly believes that women are as good professionals as men may still distrust the inputs from his female subordinates or may choose only male subordinates for his A-team that is entrusted with the most challenging and rewarding tasks. This discriminatory behavior might come from an implicit gender bias that the manager himself might be unaware of.

- The below excerpt from the article The Schmeed Memoirs by Woody Allen, about the imagined recollections of Hitler’s barber.

“I have been asked if I was aware of the moral implications of what I was doing. As I told the tribunal at Nuremberg, I did not know that Hitler was a Nazi. The truth was that for years I thought he worked for the phone company. When I finally did find out what a monster he was, it was too late to do anything, as I had made a down payment on some furniture.”

- In his book To Read a Poem, the poet Donald Hall gives the following advice to students on how to write about poems:

“The word explication originally meant ‘unfolding.’ When you explicate a literary work, you unfold its intricate layers of theme and form, showing its construction as if you were spreading it out on a table. In writing about poetry, you should most often use the tool of explication, because poems are usually dense and concentrated; take the poem word by word or line by line. Explication’s goal is to lay out in critical prose everything the author has done in a short poem or brief passage of a longer poem; the best explication goes the furthest toward that goal.

Explication does not concern itself with the poet’s life or times; it treats the work of art almost as if it were anonymous. The poet’s historical period, however, may determine the definitions of words. If the work is a century or more old, the meanings of some of its words will have changed. Because your task, as explicator, is to make explicit what the author may have put into the work – not assuming conscious intentions, but aware of possibilities – keep in mind the time when the work was written and the altering definitions of words. Thus, when an eighteenth-century writer like Alexander Pope speaks of ‘science,’ the word means something like general knowledge and not the curriculum you study as chemistry, physics, and biology. . .

Paraphrase is a necessary part of explication; it is not the whole thing. Many critics beginning an explication find it useful to summarize the action and theme of the poem as a prelude, giving a brief account of the whole before concentrating on the parts. This summary is like the beginning of a speech in a debate, which states the general conclusion the argument will lead to. . .

Meaning is not paraphrase, nor is it singling out words for their special effects, nor is it accounting for rhythm and form. It is all these things, and it is more. Meaning is what we try to explicate: the whole impression of a poem on our minds, our emotions, and our bodies. We can never wholly explicate a poem, any more than we can explicate ourselves, or another person-but we can try to come close. The only way to stretch and exercise our ability to read a poem is to try to understand and to name our whole response.”