This article is Part 2 of a three-part report on GRE acceptance in business schools.

In Part 1, I presented a data-based overview of the increasing acceptance of the GRE at most American business schools. I also talked about what an MBA-aspirant who is debating the GRE vs GMAT question could do to make a confident choice.

However, for a candidate who is anxious to present his most attractive self to a dream school, merely the suspicion that applying with a GRE score will decrease his chances of admission may make him not even consider this test. In a high-stakes situation, information by itself may not be enough to overcome fears created by misinformation. So, let us take those fears head-on now.

During my research on the GRE vs GMAT question, I kept running into three common fallacies around using GRE scores in MBA applications:

- Low GRE percentage at a business school implies GMAT preference.

- The GMAT is the safer choice because business-school admission committees are more familiar with this test.

- Submitting GRE scores signals weak intent for MBA.

In this article, I will address the first of these claims, and then the remaining two fallacies will be discussed in Part 3 of the article series.

Let’s begin!

Abbreviation notes:

- %GRE, an abbreviation first used in Part 1 of this article, should be read as ‘GRE percentage’ and means ‘the percentage of all admitted students who submitted a GRE score’

- P&Q refers to the website Poets&Quants

Fallacy 1: Low %GRE implies GMAT preference by business schools

This fallacious argument is as follows:

Premise 1: If a business school was truly impartial towards the GRE, then its %GRE would have been 50%.

Premise 2: The %GRE of most business schools is (much) lower than 50%.

Conclusion: Most business schools are not truly impartial towards the GRE (which further implies that they prefer the incumbent test – the GMAT).

P&Q has done stellar and impartial reporting on the growth of GRE in business education (it was a major source of data for me for this article series), but it still unwittingly made the above reasoning error in the following excerpt taken from an April 2020 article (emphasis added by me):

“The norm at the upper echelons remains a strong preference for the GMAT: In the top 10, the average differential between the two tests is more than 60%. The biggest gap is at UC-Davis Graduate School of Management, with 91% submitting GMAT scores and only 9% submitting GREs, but huge divides exist at much larger programs as well, including UCLA Anderson School of Management (90%-10%) and Carnegie Mellon University Tepper School of Business (90%-14%, reflecting entrants who submitted scores from both tests). The University of Chicago Booth School of Business has one of the lowest GRE percentages: 13%.”

from the article GMAT Versus GRE: The Battle For Hearts & Minds, published on Poets and Quants

What is wrong with this line of reasoning, you ask? Why do I call it a fallacy?

Well, the conclusion of this argument is properly drawn only if you assume the following:

The GRE percentage of a business school depends only on how partial the school is against the GRE.

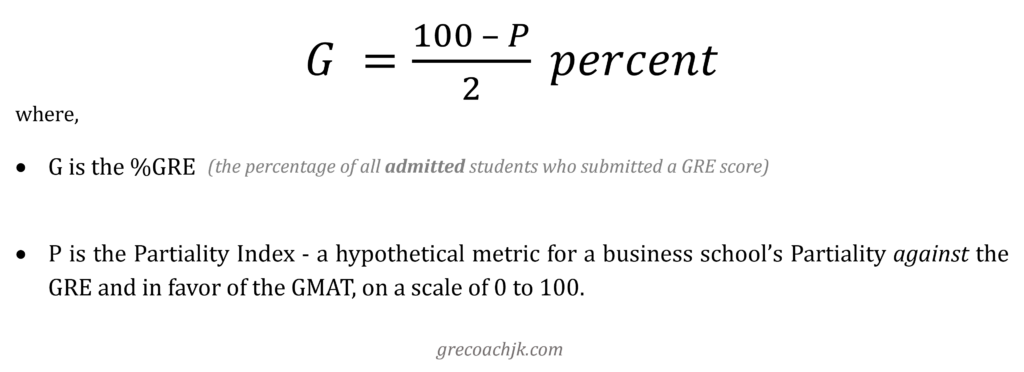

The mathematical representation of the above argument would be an equation like this one:

So, when P is 0 (a school is not partial at all), then G is 50 percent. And when P is 100 (a school is fully partial against the GRE, to the point that it does not accept the test at all), then G is 0 percent.

As this is a linear equation, not only can we find the value of G by using the value of P, but we can also do the converse: deduce the value of P from the value of G. For example, if in the above equation, you put in G = 10 percent, then you find out that P must be 80. A P-value of 80 is quite high; it indicates significant partiality against the GRE.

Now, it is only by assuming that G is indeed a function of P and of P alone that you can use a school’s G-value to make confident claims about that school’s P-value.

What do you think about this assumption? Do you think it likely to be true?

Consider two arguments that are analogous to Fallacy 1:

- Low percentage of women in the labor force working at a construction site implies that the foreman of the project is a male chauvinist.

- You do not own a dog; so, you are a cat person.

These two claims sound patently absurd, don’t they? From our knowledge of the real world, we know that many factors other than a foreman’s chauvinism could fully explain the low proportion of females at a work site. Likewise, cat-preference is far from the only reason why a person would not own a dog.

Coming back to Fallacy 1, could %GRE also depend on factors other than a school’s Partiality Index?

One possible factor does come to mind: the lower percentage of GRE among the admits could merely be the reflection of a lower percentage of GRE among the applicants! Is it not possible that many business-school applicants decide to stick to the safe choice – the GMAT – because all the speculation around the GRE makes it seem too risky? That is, it might be the applicants (and not the schools) who prefer the GMAT over the GRE.

An anecdote related by Dee Leopold, former Managing Director of MBA Admissions at the Harvard Business School (HBS), corroborates this hypothesis about the applicants’ tendency to play it safe.

For the admissions cycle of 2013-2014 (for Class of 2016), the HBS application package included just one essay and the school made it clear that this essay too was optional (in contrast, just three years ago, HBS had required four mandatory essays).

9543 applications were received in that cycle. Can you guess how many applicants had been brave enough to actually not submit an essay?

Only ten.

Among these ten, one was admitted – the acceptance rate, 10%, was effectively the same as the 12% rate for the essay-submitting applicants.

10 out of 9543 is 0.1 percent. 99.9 percent applicants apparently did not trust that HBS knew its own mind; they probably feared that even though the school had explicitly told them that it was okay to not submit an essay, it would still judge them adversely for believing what it had said and actually not submitting an essay. There was no downside to submitting an essay while there might be a downside to not submitting it. When the decision that faced the applicants is framed like this, it seems most natural that almost everybody chose to submit an essay.

Similar risk-aversion might be at work in the context of GRE vs GMAT, and so, the low percentage of GRE Submitters among the admits might be nothing more than the natural result of a low percentage of GRE Submitters among the applicants.

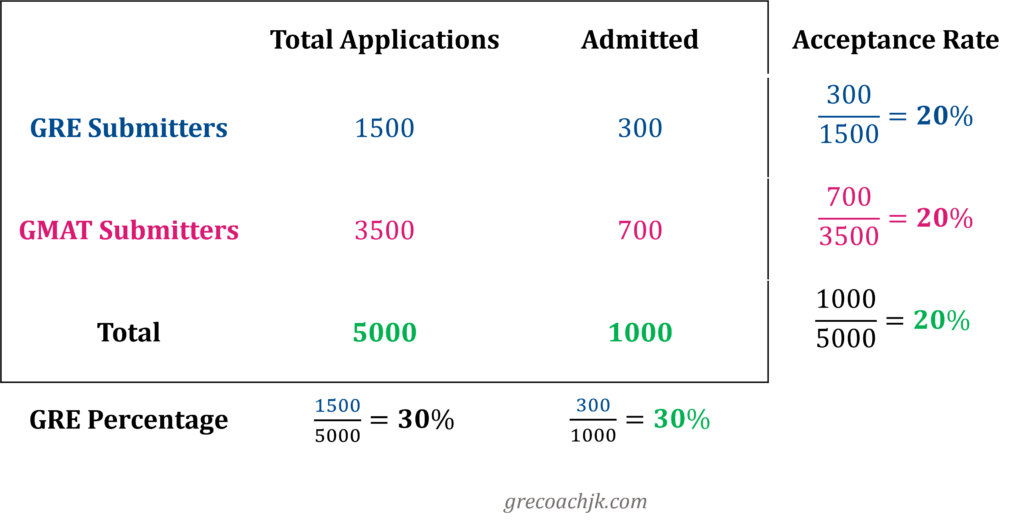

How can we test this possibility? Imagine a hypothetical business school whose admission statistics are as follows:

Is this school truly test-agnostic?

“Yes,” we would say. The figures speak for themselves: the acceptance rate for GRE Submitters is the same as that for GMAT Submitters; another way of making the same point – the GRE percentage is the same among the admits and the total applicants.

The trouble is that no school shares all this information. The only data-points relevant to our discussion that business schools share are the ones in green:

- the total number of applications

- the overall Acceptance Rate of a school, and

- the %GRE among the admitted students.

You see the problem? We do not get to know if the Acceptance Rate differs with the choice of standardized test, or if the %GRE among the admitted students is more or less than the percentage of GRE Submitters among all applicants.

There was one time though when a business school did share this data. It was none other than the Harvard Business School!

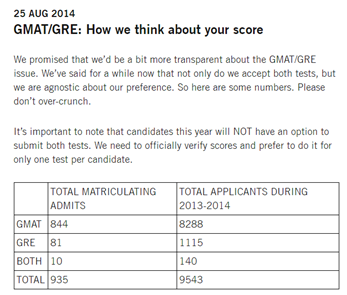

Dee Leopold (also mentioned a few paragraphs ago) wrote an official blog post snapshotted below (I could not find it now on the HBS blog; so, I took recourse to the Wayback Machine):

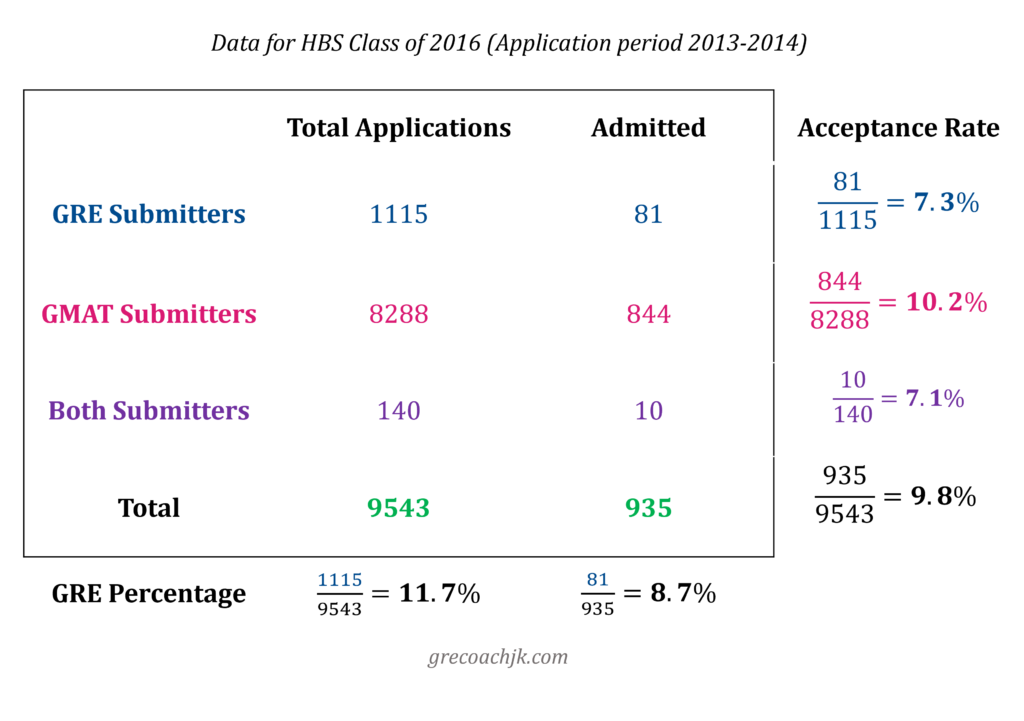

The term Matriculating Admits in this table means those people who accepted their admission offers and enrolled at HBS.

The acceptance rate of HBS for this admission cycle was 12%. So, we can infer that the number of applicants to whom HBS rolled out admission offers was 12% of 9,543 = 1,145; these successful applicants are also called ‘Admits.’ Therefore, for this cycle, HBS had 1145 Admits, out of which 935 chose to become Matriculating Admits. The remaining (1145 minus 935 equals) 210 Admits may have chosen other business schools or deferred/cancelled their MBA plans.

Let us (against the advice of Ms. Leopold in the above blogpost 😊) crunch these numbers:

We note that there is indeed a 3-percentage point difference between the Acceptance Rates for GRE and GMAT (7.3% and 10.2% respectively). The GRE percentage among the Admits is 11.7%, which also is 3-percentage points lower than the GRE percentage among the total Applicants.

But is this 3-percentage point difference significant?

The admissions director prefaced the data thus:

“We’ve said for a while now that not only do we accept both tests, but we are agnostic about our preferences. So here are some numbers.”

Ms. Leopold seems to have regarded these numbers as proof of her impartiality towards the two tests. This seems to indicate that she did not think much of the 3-percentage point difference between the figures for the two tests.

In another Poets and Quants article from 2014, I found this quote from Bruce DelMonico, then the admissions director at Yale SOM and now the school’s Assistant Dean for Admissions:

“[At Yale University’s School of Management, there is little difference in the admit rates between applicants who do either test.] We do go back and calculate acceptance rates on our enrollment students, and every year we find that we accept GRE test takers at the same rate as GMAT test takers.”

Both the HBS table and the above quote about Yale SOM make us realize that it is fallacious to use the lower %GRE (with respect to the GMAT) among the students admitted at top business schools as an automatic proof of the schools’ partiality against the GRE (and in favor of the GMAT). If a school explicitly states that it is impartial between the GRE and the GMAT, then, if it has low %GRE, this is mostly likely to be a mere reflection of the lower GRE percentage among the applicants.

In Part 3 of this article series, I will address the remaining two fallacies around GRE use in MBA applications:

- Fallacy 2: The GMAT is the safer choice because business-school admission committees are more familiar with this test.

- Fallacy 3: Submitting GRE scores signals weak intent for MBA