This is the third and concluding part of an article series on the acceptance of GRE at business schools.

During my research on the GRE vs GMAT question, I kept running into three common fallacies around using GRE scores in MBA applications:

- Low GRE percentage at a business school implies GMAT preference.

- The GMAT is the safer choice because business-school admission committees are more familiar with this test.

- Submitting GRE scores signals weak intent for MBA.

I have already addressed the first of these in Part 2 of this article series. In this article, I will talk about the remaining two.

Fallacy 2: The longer familiarity of admission committees with the GMAT makes it the safer choice.

This argument about why an MBA-enthusiast should choose the GMAT over the GRE goes like this:

Business school admission committees have been using the GMAT for much longer than the GRE. So, they are more familiar and comfortable with the GMAT scoring scale. Even the ETS (the organization that owns and administers the GRE) knows this – they have provided a GRE-to-GMAT score convertor to make it easier for business schools to understand a GRE score. By choosing the substitute (GRE) over the original (GMAT), an applicant risks her score being misunderstood/ununderstood by the admissions committee.

It is true that many MBA-aspirants convert the GRE scores into their GMAT equivalents to understand them better. It is quite likely that business school admission committees also do this, at least in their initial experience with the GRE. However, the GRE-to-GMAT score conversion is fairly straightforward and needs to be done only a few times before one develops quick rules of thumb for the GRE scores.

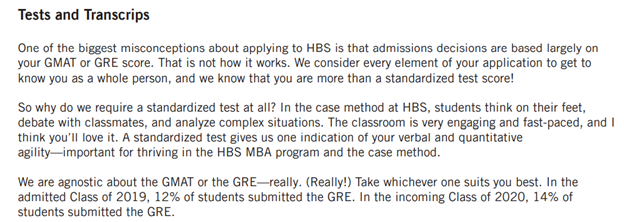

Let us guesstimate how many GRE applications have already been processed at business schools and, therefore, whether any risk still remains that an admission committee may not know how good or bad your GRE score is.

Take Harvard Business School, a school that has warmed to the GRE slower than most business schools. We have already seen (in Part 2 of this article series) that in 2013-2014, HBS had 1115 GRE-submitting applicants, and the %GRE (percentage of GRE Submitters among admitted students) was 8.7%. For this one year alone did we have the data to calculate that the percentage of GRE submitters among applicants was slightly higher than that among admits. As we do not know the percentage of GRE submitters among applicants for any other year, let us work with the approximation that the percentage of GRE submitters among applicants is EQUAL TO %GRE (which is a data-point that HBS does share). This assumption allows us to estimate the number of GRE submitters at HBS over the last 7 years. For 2015 and 2016, since the %GRE data is not available, we can assume the same number as from 2014. We are only interested in a rough ballpark number here, not exact calculations.

These year-wise number of GRE submitters add up to 9963. So, roughly speaking, by 2021 the HBS admissions committee had already evaluated around ten thousand GRE scores. Is it likely that the admission officers would still fumble around GRE scores? Keep in mind that these are people who seem to have no problem in making sense of completely diverse profile markers (just think of the wide variety of education backgrounds, career choices and countries of origin and operation that would feature in the applicant pool of any top business school).

When the GRE first began to get accepted at business schools, in those initial years, the argument that it was safer to stick to the GMAT because of possible familiarity bias among business school admission officers in favor of that test might have been valid. That time is long gone. GRE has been accepted at most schools for so long now that this argument does not seem plausible anymore.

Fallacy 3: The GMAT ‘shows intent’

During my research on the GMAT vs GRE question, I found that the following argument in favor of the GMAT was also common:

One of the criteria that impacts business school rankings is the percentage of a school’s admission offers that get accepted by applicants. A high percentage is good for a school’s rank. To keep this number high, schools try to not make admission offers to candidates who are likely to reject them. Given this context, if you choose the GRE, which is a general test, business schools may think that you are keeping your options open beyond an MBA, and apprehensive that you may reject them, they may not make you an offer at all. You should stick to the GMAT, a management-specific test; this choice will convince the schools of your commitment to pursue an MBA.

The above argument is correct in the following particulars:

- Schools do try to gauge an applicant’s intent to join their program.

- Schools do care about their rankings.

- The ranking of a school does get impacted if many students reject its admission offers.

However, the argument is fallacious because ‘showing intent about studying management’ is not the same thing as ‘showing intent about studying management at this particular school,’ and it is the latter that a school actually cares about.

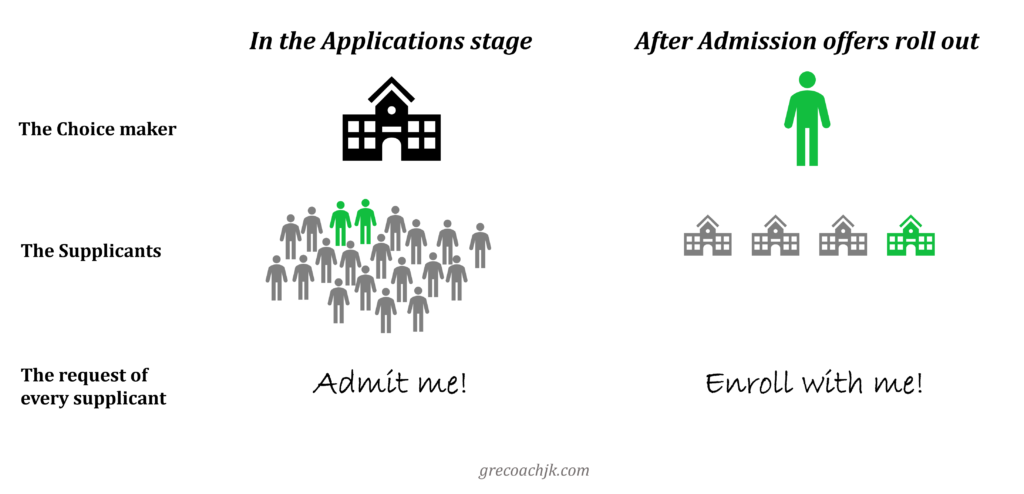

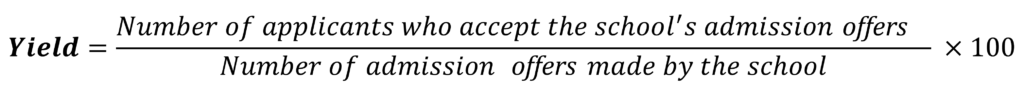

Business schools – and the organizations that rank them – measure two metrics to determine their brand power:

- their Acceptance Rate (the percentage of all applicants to whom they offer admission), and

- their Yield Rate (the percentage of all admission offers that get accepted by applicants).

Many applicants keep track of their conversion ratio – the ratio of admission offers received to the total number of applications made. A conversion ratio that is close to 1 would be a huge confidence-booster for anybody. The same goes for schools. If a school offers admissions to 400 applicants and all of them accept its offer, then this statistic would indeed indicate the school’s awe-inspiring clout among applicants. For the record, there is no such school. The best consistent record till date is held by the Harvard Business School which manages to convert about 90% of its offers into enrollments.

So, the Yield rate of HBS is 90%. This also means that every year, about 10 percent of the people to whom HBS offers admissions decline to join, presumably because they get a better offer from other highly ranked business schools (Wharton, Stanford GSB etc.) or because they drop/defer their MBA plans altogether.

A low yield of a school hurts the school’s rankings and reputation. It indicates:

- poor faith in the school among the candidates whom the school wants (the school loves them, but they don’t love it back – ouch!), and/or

- poor judgement of the school’s admissions committee – it failed to accurately gauge the seriousness of the applicants in joining that school.

So, yes, each admission committee tries it best to keep its school Yield high. It tries to get a sense of whether an applicant is passionately interested in the school (implies a high likelihood of accepting an admission offer) or regards the school as nothing more than a fallback option, one that he will ditch without a second thought if he gets a more attractive offer.

For some candidates, this ‘more attractive offer’ could be for a MS/PhD program, while for others, it could be for an MBA program at another school. Think of the people in your own circle who are considering an MBA; how many of them are also seriously considering other degree programs like an MS or a PhD? If you extrapolating that ratio to all MBA applicants, which of the following two worries will you say is likely to be bigger for a business school?

- Losing its admits to a different degree program

- Losing its admits to another MBA program

Your choice of the GMAT over the GRE does nothing to assuage this second worry of a school.

So, know that an admissions committee will carefully evaluate the seriousness of your intent to join their program regardless of your choice between the GRE and the GMAT. It keeps track of micro-behaviors such as the following to gauge your ‘demonstrated interest’:

- Did you register with them for email updates?

- Did you open all their emails?

- Did you visit the campus and attend their info webinars etc.

- How personalized to their school were your submitted essays and/or interview responses?

It is when your fare poorly on behavioral metrics such as these that an admission committee sees you as a non-serious applicant.

As I was writing this, I remembered that in an interview that I had conducted with Shruti Parashar, an eminent admissions consultant, I had asked her what mistakes she would caution an applicant to avoid. The below excerpts from her response to this question are relevant to our present discussion:

“The schools abroad are very upfront. They will call a spade a spade and you be ready to listen to what they are saying. . .

You need to give ample time to put your stories together. Look at what the school wants. Don’t rush in with the same application everywhere. Every school on their website gives a clear mission statement. It is not just for marketing; they actually believe in it. You have to understand who goes to a particular school; why are they going to that school. For example, Emory Goizueta often say that they choose to be a small school. It’s not that they are just trying to cover up their being small; they actually operate in that manner; everything in the school is aligned to that choice about size.

So, if you can relate to those values and you can showcase those values in your application, that is going to add value to your candidature as an applicant. Put yourself in the shoes of the admissions committee of a school; if they see two candidates with similar credentials but one candidate is committing to the objectives and values of the school while the other has not spoken about them, then they will be more likely to choose the first one.

A mistake that I see many Indian applicants make is that they do not interact much with the schools they are applying to. Even when they have questions or doubts, they refrain from asking the school directly. And, if they do write and the school answers them, they do not always trust that answer. For example, take the question of whether a business school will disadvantage you for applying with a GRE score instead of a GMAT one. Trust them on what they tell you. Do not fear that despite telling you that they are test agnostic, they will secretly be biased against you due to the GRE. It is your bias – you are not able to comprehend what else they want in the profile, and you are just banking on the GMAT or the GRE score to get you there. You have to understand that every aspect of your application is important.

Schools do value the interactions that you have with them during the application process and the number of sessions that you are attending. For example, Virginia Darden has, over the last year, done so many workshops on the small essay questions, the long essay questions, the recommendations, the interview, everything. So, if you are serious about applying there, then you would be there at each of these events. That’s the best way to learn what the school wants. This is also how you will get to know the opportunities for scholarships, or you’ll get to know which alumni to connect to. If the school is recommending something, then you should take it up. Schools do spell these things out. Also, this demonstrated intent will make the school more favorably disposed towards you.

At GOALisB, we instruct all our international applicants to mandatorily attend all events of the schools that they are serious about and to keep connected with the school staff. You should budget this time when deciding your application timeline.”

Conclusion

During my research for this three-part article series, I discovered a lot of misinformation and anxiety around the GRE vs GMAT question. The data that I shared in Part 1 of the article series enables us to make a general statement that about 90 percent of all business schools in the US will happily accept GRE scores. The way to be 100 percent sure about the stance of your target schools regarding the GRE is to ask them about it. And once they answer your query, trust them on it! In Parts 2 and 3, I hope to have addressed some of the fallacious arguments made against the GRE.

Let us give the last word to Chad Losee, the Managing Director of Admissions at Harvard Business School. Here is the advice that he gives in a 2018 PDF titled ‘Application Tips’: