“How do I it make it easier to learn so many new words for the GRE?”

“I keep tripping on words that have multiple meanings or connotations that I had no idea about. How to fix this?”

I got asked these two questions recently. My advice is to follow the tips shared in this article:

- Choose your learning source wisely.

- Do not make lists of synonyms/antonyms your primary source for GRE vocab.

- Make your own GRE Wordbook.

- Seek dramatic usage examples (through ChatGPT, online dictionaries or Goodreads quotes).

- Read.

- Pick words in bunches of relatedness.

- Revise regularly.

- Say out the words aloud.

- Talk about words with your friends.

- Be the tortoise, not the hare.

Before we talk about the remedy, however, it is important to understand the cause of the disease.

Why is learning GRE words so hard?

Among students who need to devote a major chunk of their GRE prep time to vocab acquisition, many do not have a prior habit of reading newspapers, magazines, or non-curricular books in English. Upon starting their GRE prep, they suddenly find themselves in the midst of a storm with strange, tough words whirling all around them. What to do now?

Perhaps they do a Google search for “How to improve vocabulary for the GRE?”, find a GRE word list in the search results and start to memorize the words one by one. The issue is that most word lists just provide the word and its definition and/or its synonyms/antonyms. For example, here are three entries taken from different sources for the GRE word ambiguous:

Source 1: “Ambiguous – doubtful; uncertain”

Source 2: “Ambiguous – not clear, hard to understand, open to having several meanings or interpretations”

Source 3: “Ambiguous – (adj) having more than one possible meaning. Usage examples:

- ambiguous words;

- Frustrated by ambiguous instructions, the parents were unable to assemble the toy.”

How will you rate the ease of learning this word from these three sources? My take: Source 1 will be the hardest to learn from, because it just offers dry word-meanings, and Source 3 will be the easiest, because it provides an easy-to-understand meaning and an easy-to-imagine usage example.

In fact, Source 1 does not even do a very good job of conveying the exact idea behind ambiguous.

- If I am uncertain about whether to vote in favor of or against a policy, can I also say that I am ambiguous?

- If I think that a marketing claim is doubtful, can I also say that the claim is ambiguous?

The answer to both these questions is ‘No.’

The doubt or the uncertainty that is conveyed by the word ambiguous is of a specific type: about which meaning or interpretation to choose out of the multiple possibilities. In the example sentence for Source 3, the parents were unable to assemble the toy because the written instructions could be understood in more ways than one. For example, the first step in the pictureless, text-only manual might have been,

“Lay the red block on its side and the green block perpendicular to it.”

This would have left the poor parents uncertain about which of the three possible sides of the cuboidal red block was meant by the manual: length*breadth, breadth*height, or length*height? Further, the green block could be placed perpendicular to the red block in many different configurations. Which one of those did the manual mean? (No wonder the parents failed to assemble the toy!)

A student learning his GRE words from Source 1 would not only have a harder time memorizing the words (because there are no usage examples that can serve as memory-aids) but also form an incorrect idea of the word.

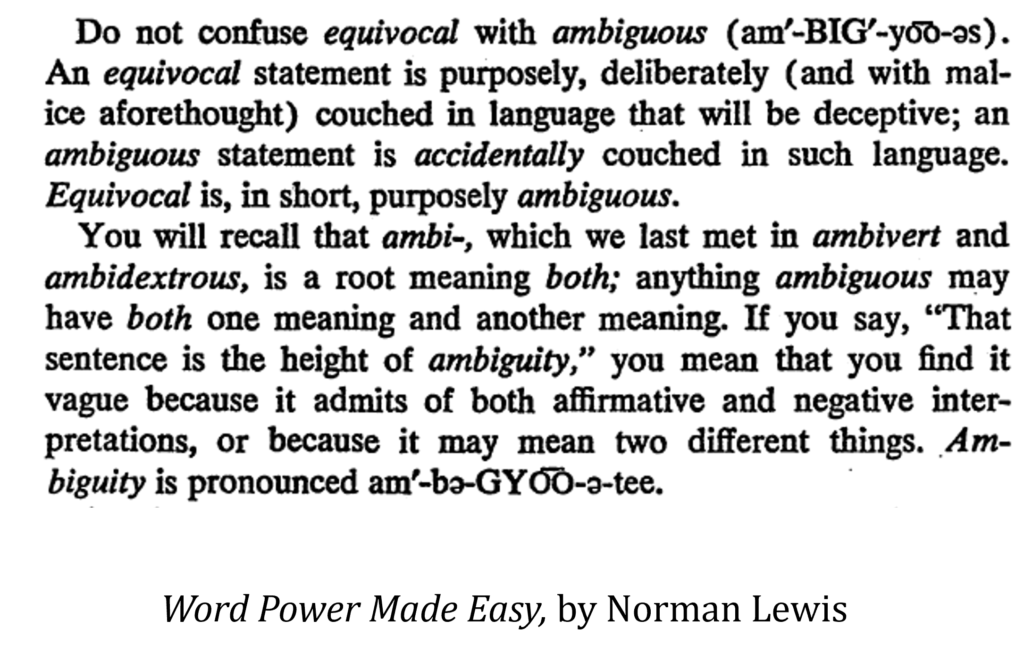

Now compare the above three sources with Source 4: Word Power Made Easy

Here, the author is talking to you, which makes the learning experience feel intimate. He also preempts a possible confusion with another word through a clear explanation of the difference between the two words.

Finally, here is how I teach ambiguous in my GRE Vocab Program. Let’s call this Source 5.

How will you rank the five sources that we have discussed above, in ascending order of learning ease?

The takeaway from our discussion thus far is that the source that you are learning from matters.

1. Choose your learning source wisely

If you find that you keep forgetting most of the words that you learn or that you remain ignorant of the nuances/connotations of the words you have memorized, then you may need to replace the source you are studying from.

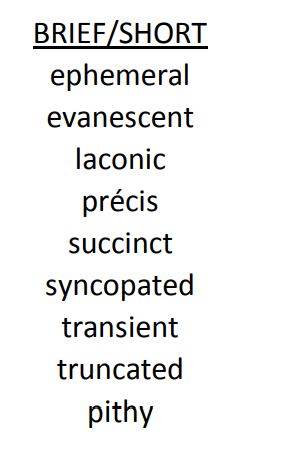

Irrespective of how you or I rank them, the five sources discussed above have one good thing in common – they provide the meaning of each word. I have also seen floating online some GRE vocab documents that merely provide a laundry list of synonyms or antonyms. Below is a snapshot taken from one such PDF.

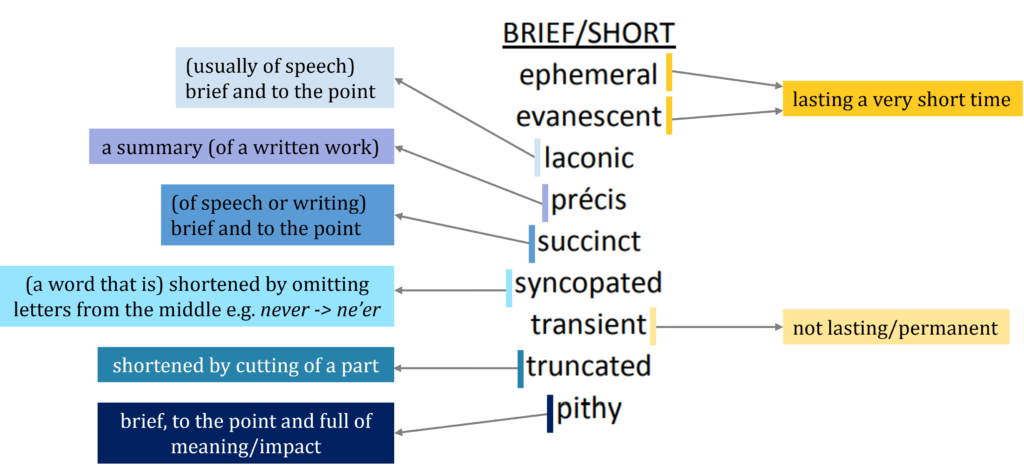

Is this list helpful? Let us see. Here is what these words mean:

We find that the nine words in the list map to two distinct groups:

- The yellow words are about briefness or shortness in lifespan, while

- The blue words convey briefness or shortness in spoken or written expression.

Within the yellow group, I have put transient in a different shade because it is not an exact synonym of ephemeral and evanescent. In the blue group, no two words are exact synonyms; so, I’ve shown all these words in different shades of blue.

Leave aside sensitizing a student about intra-group shade variations, the original list does not even indicate that it contains two idea groups that are as distinct and non-synonymous as the colors blue and yellow. Would you be surprised if the unsuspecting student who picked up his GRE words from this list gets word connotations wrong? Therefore, my second tip is this:

2. Do not make lists of synonyms/antonyms your primary source for GRE vocab

My third tip is to:

3. Make your own GRE Wordbook

By Wordbook, I mean your personal collection of difficult words that you come across in your study of GRE official material and other vocab sources. To make revision quicker and easier, aim to make this document your single reference resource for GRE vocab, to the extent possible. So, if, for example, you are following my GRE Vocab Program, then your mind-maps for the day-wise words should be recorded in the Wordbook.

I, and some of my students, use physical notebooks and flashcards to store words, while my other students use digital documents, sheets or flashcard apps. Choose the format that works for you.

What should a word-entry in your Wordbook contain? The word meaning, yes, but not just that. Recall Sources 1 to 3 for the word ambiguous. Among them, why had the third source felt the easiest to learn from? Because not only did its usage sentence ably convey the meaning of the word, but also parents scratching their heads over ambiguous instructions and ultimately failing to assemble the toy was a scene that we could easily imagine, found interesting, and, therefore, were likely to remember. Find such sentences for your Wordbook.

4. Seek dramatic examples

If you keep forgetting certain words despite repeated revisions, look for better usage examples for them. To do so, you may use ChatGPT or online dictionaries.

ChatGPT

In my experience, searching for good usage examples for the words you are learning is a time-consuming task. You may have to read perhaps ten usage examples to find two that appeal to you.

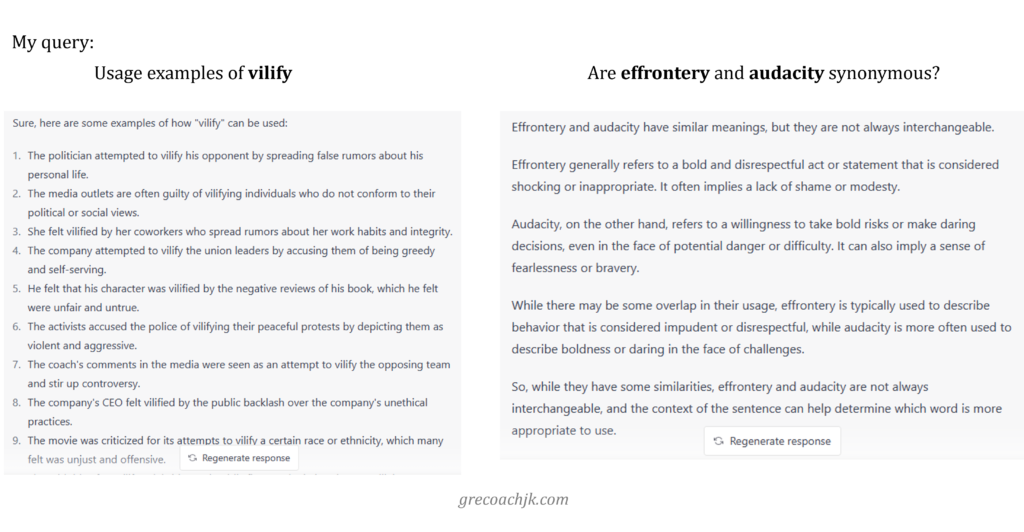

You can save quite some time by asking ChatGPT to generate usage examples for a particular word. Out of the list of sentences that it generates, copy the most dramatic ones to your Wordbook. You could keep regenerating the responses till you are satisfied.

You could also ask it to clarify if two words can be used interchangeably. Both these use-cases are exemplified in the image below.

ChatGPT may also help you with your semantic mind-worms: the niggling “what was that word?” queries that keep whirling in your brain around words you can now recall only dimly. For example, I recently came across a beautiful new word in an online article and looked it up; it meant lament. I meant to record this new word in my Wordbook the next morning but failed to do so. A few days later, I realized that I had forgotten its spellings. I tried combinations like ‘theoderny’, ‘thederny’ and ‘theodorny’ but neither Google nor online dictionaries could guess what I meant.

When I searched on ChatGPT for “a synonym of ‘lament’ that starts with ‘th’,” I found my word:

“One synonym of “lament” that starts with ‘th’ is “threnody.” A threnody is a song, poem, or other piece of music that expresses grief or mourning. It is often used in reference to funerals or other solemn occasions.”

In such ways, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in your vocab learning.

Online Dictionaries

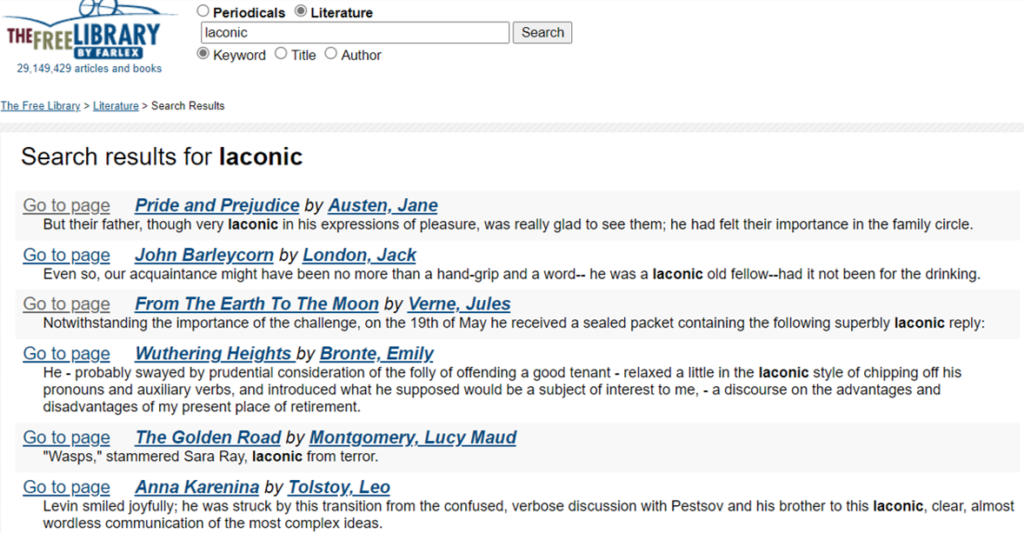

Quality online dictionaries that are also free are freedictionary.com, dictionary.com, merriam-webster.com, and dictionary.cambridge.org. All of them provide sample phrases or sentences right next to the word-meaning and, after the explanation, list many more usage examples. For example, when you look up a word on freedictionary.com, scroll down to the end of the page and you’ll find references to the word in classic literature. Below are the sentences that come up for laconic.

Jot down the one or two examples that you like best. The characteristics of a good usage sentence are:

- it is a clear and vivid communicator of the word-meaning.

- you enjoy it and can easily imagine the situation it describes.

Add the chosen sentence(s) to your Wordbook.

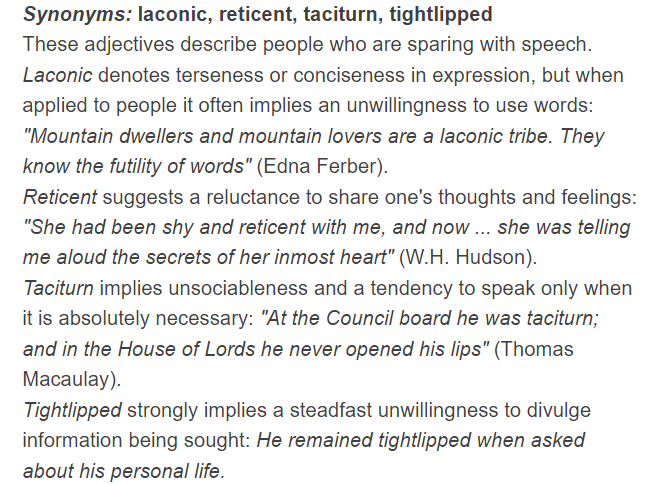

Using dictionaries has an added advantage: word usage notes. Lexicographers (people who write dictionaries) take pains to clarify the nuanced differences between similar words. For example, consider this comment on the page for laconic on freedictionary.com:

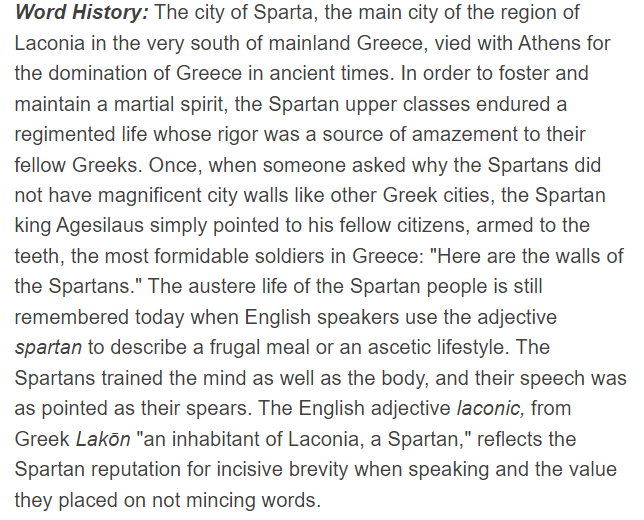

Dictionaries also share colorful etymological histories, where relevant. For example, here is how the word laconic came about.

In the snapshotted note, the word spartan is associated with:

- “a regimented life whose rigor was a source of amazement” to other people,

- an austere life,

- a frugal meal, and

- an ascetic lifestyle.

You may want to write down these associations in your Wordbook (this is how to organically build your own list of synonyms and antonyms, one much superior to the type of lists discussed for Tip 2). We also learn that laconic = spartan speech (strict and disciplined use of words; speech that is “as pointed as . . .spears” and incisively brief). Our understanding of laconic improved with knowledge of its origin.

For a word that keeps tripping you up even after you’ve consulted dictionaries, here are two more ideas:

- Find its translation in your mother-tongue. For example, if you are a Hindi speaker and cannot remember the word ascetic, realizing that it simply means yogi, fakir, rishi may solve the problem.

- Search it on goodreads.com and attend to the ‘quotes’ section of the results. Note down the quotes that you find interesting or amusing. For example, when I did this for laconic¸ the following two samples stood out to me:

“You can get far in North America with laconic grunts. “Huh,” “hun,” and “hi!” in their various modulations, together with “sure,” “guess so,” “that so?” and “nuts!” will meet almost any contingency.”

Ian Fleming (For Your Eyes Only (James Bond, #8))

“Everything you wanted to say required a context. If you gave the full context, people thought you a rambling old fool. If you didn’t give the context, people thought you a laconic old fool.”

Julian Barnes (Staring at the Sun)

5. Read

The easiest way of improving your vocabulary is reading.

I still remember my first encounter with the word pulverized almost twenty years ago while reading A Suitable Boy. Before I share that scene, I’ll give you some context. The novel’s heroine Lata attends university in Brahmpur. Her oldest sibling Arun, second brother Varun, and Arun’s wife have come there on a short visit from Calcutta for a wedding. Arun is the sole breadwinner of the family, while Varun is a nervous young man who studies in Calcutta University and lives in Arun’s flat. Right before this scene, the married couple has been going on about how utterly crass and unfashionable Brahmpur and its people were.

‘I’m enjoying it here,’ Varun ventured, seeing Lata look hurt. He knew that she liked Brahmpur, though it was clearly no metropolis.

‘You be quiet,’ snapped Arun brutally. His judgement was being challenged by his subordinate, and he would have none of it.

Varun struggled with himself; he glared, then looked down.

‘Don’t talk about what you don’t understand,’ added Arun, putting the boot in.

Varun glowered silently.

‘Did you hear me?’

‘Yes,’ said Varun.

‘Yes, what?’

‘Yes, Arun Bhai,’ muttered Varun.

This pulverization was standard fare for Varun, and Lata was not surprised by the exchange. But she felt very bad for him, and indignant at Arun. She could not understand either the pleasure or the purpose of it. She decided she would speak to Varun as soon after the wedding as possible to try to help him withstand —at least internally—such assaults upon his spirit. Even if I’m not very good at withstanding them myself, Lata thought.”

From chapter 1.4 of A Suitable Boy, by Vikram Seth

From the context clues, I guessed that pulverization meant getting bullied or scolded like a child. To confirm, I consulted my dictionary and found that it is the action of crushing into a powder or dust. And I just went “wow!” at Seth’s playful but perfect word-choice. Seen in the light of this meaning, the image of Arun “putting the boot in” became even more vivid– I could see poor Varun lying on the ground, Arun crushing him into dust with his boot. To this date, I remember both this scene and the word pulverization.

Now that you are earnestly preparing for the GRE, try to read at least one book per month. It may be a book related to your profession or to your interests or a novel in a genre you like, really anything is fine as long as it helps you with GRE vocab. How to know if it will? Check the number of unfamiliar/GRE words on three random pages. If the average number of such words per page is between 2 and 6, then the book should be useful. You want your books to have a lot of interesting and easily understood context around the tough words. A too high density of hard words is as enjoyable as a machine gun firing at you, thuck-thuck-thuck-thuck without respite. We don’t stick to what we don’t enjoy.

What should you do when you encounter a new word in your reading? I like to write it down in my Wordbook along with context from the book – the word-containing sentence alone or along with surrounding sentences. But, when time is short, I do as Norman Lewis suggests below. His advice works, not only for novels but for all books:

“The natural temptation, when you encounter a brand-new word in a novel, is to ignore it-the lines of the plot are perfectly clear even if many of the author’s words are not. I want to counsel strongly that you resist the temptation to ignore the unfamiliar words you may meet in your novel reading: resist it with every ounce of your energy, for only by such resistance can you keep building your vocabulary as you read.

What should you do? Don’t rush to a dictionary, don’t bother underlining the word, don’t keep long lists of words that you will eventually look up en masse-these activities are likely to become painful and you will not continue them for any great length of time.

Instead, do something quite simple – and very effective.

When you meet a new word, underline it with a mental pencil. That is, pause for a second and attempt to figure out its meaning from its use in the sentence or from its etymological root or prefix, if it contains one you have studied. Make a mental note of it, say it aloud once or twice – and then go on reading.

That’s all there is to it. . . you will begin to notice the word occurring again and again in other reading you do, and finally, having seen it in a number of varying contexts, you will begin to get enough of its connotation and flavor to come to a fairly accurate understanding of its meaning. In this way you will be developing alertness not only to the words you have studied . . . but to all expressive and meaningful words. And your vocabulary will keep growing.

But of course that will happen only if you keep reading.”

From Session 41 of Word Power Made Easy, by Norman Lewis

6. Pick words in bunches of relatedness

A bunch of grapes is easier to put on your plate than the same number of individual grapes. So it is with words.

When you read an article or a book, you learn words that all hang from the same twig – they are joined together by the same scene or context. For example, if the words venture, glare, glower, indignation, and pulverization were all new to you, compare the experience of learning them through the scene quoted above from A Suitable Boy with that of learning them as five standalone words in a vocab list, where each word had its own usage sentence that was utterly unrelated to the usage sentences of any other word.

In Word Power Made Easy, Norman Lewis uses two types of relationships to bunch words together – thematic and etymological. He starts a session by listing ten words that describe different ideas related to one theme. For example, the theme for Session 1 is ‘personality types,’ and the chapter begins with 10 words that describe distinct personality-types. These are words like egoist, egotist, altruist, introvert, extrovert, ambivert etc. Then, in Session 2, he takes up the root ego from the first two words, explains it, and lists other words from that root; then he does the same for the root alter on which altruist stands. This is a brilliant method to teach vocabulary, because in each session, you learn words that are in some way related to one another or to previously learnt words.

In my GRE Vocab Program too, words are interconnected through a common context, theme or etymology. For example, the theme of Day 1 is ambiguity in language. I open with a quote that describes the inherent ambiguity of language. The quote contains the word apprehensive, the first word taught. I then explain ambiguity in detail, using the example of a legal case fought around the definition of ‘chicken’, and in this discussion, the words univocal, equivocal, unequivocal and discrepancy naturally come up. So, you learn a bunch of five words related to the idea of ambiguity.

Interrelated words are easier to learn than isolated words.

7. Revise regularly

You probably already do revise your words but allow me to nevertheless reiterate the absolute necessity of doing so. No matter how well you understood a word in your first meeting, without periodic review, a faint trace may be all that’s left of it a month later.

When revising a word, focus less on its dictionary definition and more on the dramatic scene that your usage sentences convey. See if you can recall that scene on your own first without looking at your Wordbook. If you remember that Lata had felt indignant at how Arun routinely bullied Varun and that she had resolved to boost Varun’s confidence; you know that indignation roughly means to mind/dislike a wrong being done and thinking/asking, “How can he do such a thing!” Such a guesstimate is good enough.

If, during your revision, you find yourself confusing two words – for example insidious with invidious, disinterested with uninterested, militate with mitigate, revile with regale etc. – then, write cautionary notes to this effect next to your Wordbook entries for these words. It may also help to devise easy mnemonics to tell the two confusables apart.

8. Say out the words aloud

It helps to say out loud the words and sentences you are learning. Adding your voice to the learning mix makes for richer, multi-dimensional memories. Look up the word pronunciations online and note the tricky or unexpected ones so that you say those words correctly from hereon.

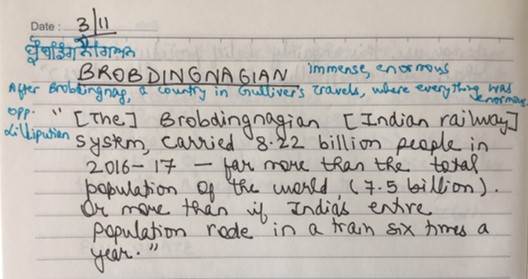

How to write down the sounds? Phonetic symbols are of course one way. But the idea that I generally use is to write the spoken English word in my mother-tongue, Punjabi. For example, here is a snapshot from my Wordbook. When I first encountered the word Brobdingnagian in an article, I thought the -nag- part of it sounded like ‘page’ or ‘age.’ But I found that it rhymes with ‘rag’ or ‘tag.’ So, I wrote the actual sound of the word in Punjabi spellings, from which I can recreate the spoken word unambiguously. You may try the same with your mother-tongue.

Another way to convey the correct sound to your future-self may be to write ‘~ rag’ above the -nag- part of the word.

9. Talk about words with your friends

Pick your friends’ brains and gain from their reading and knowledge. For a word that you keep forgetting, ask a friend if they know it, and if they do, what associations does that word evoke in their mind?

For example, if you were a friend who asked me this question for the word pulverized, I would have described the scene quoted above from A Suitable Boy. And perhaps that scene (or my telling of it) would have amused you and become associated in your mind with the word.

My final tip applies not to learning GRE vocab alone but to GRE prep in general.

10. Be the tortoise, not the hare

Assume that at the rate of 40 minutes per day, you can master 300 GRE words in a month. So your input time for vocab will have been (40 minutes per day)*(30 days per month) = 1200 minutes = 20 hours that month.

Now, imagine that instead of being such a tortoise, you did no vocab for three weeks, then, on the twenty-second day, you sat on your table at 9 AM sharp, opened the 300-words list and kept at it for 24 hours straight till 9 AM the next morning. For the remaining eight days, you stayed away from vocab.

The hare may claim to have worked harder than the tortoise (24 hours of monthly study time vs 20 hours). But will an exhausting binge impress the GRE? The winner of the GRE race will be the one who performs better in a test taken for those 300 words on the first day of the next month. Who do you think will it be, the hare or the tortoise?

I have discussed the importance of regular but moderate effort in greater detail in this article: The tortoise, Trollope and GRE Prep

Conclusion

I have shared the following tips for learning GRE vocab in an intelligent manner. It is through such attentive engagement with seemingly tough words that you will turn them into loyal and intimate friends, always at your beck and call.

- Choose your learning source wisely.

- Do not make lists of synonyms/antonyms your primary source for GRE vocab.

- Make your own GRE Wordbook.

- Seek dramatic usage examples.

- Read.

- Pick words in bunches of relatedness.

- Revise regularly.

- Say out the words aloud.

- Talk about words with your friends.

- Be the tortoise, not the hare.

Your pursuit of higher education indicates that you desire to soak in new ideas, perspectives, and frontiers of knowledge. Why wait till the start of a degree program for such intellectual stimulation when you can enrich your mind today by using the GRE words as gateways to fascinating new knowledge? Good luck!