This article describes a time tracker that I have created for the GRE quant section. I’ll also then tell you the story of the student whose timing problems roused me into creating this simple tool. With this time tracker, you can avoid the situation where you spend too much time on some questions earlier in a section and then run out of time for the last few questions.

Watch the below video to get the gist of my time tracker.

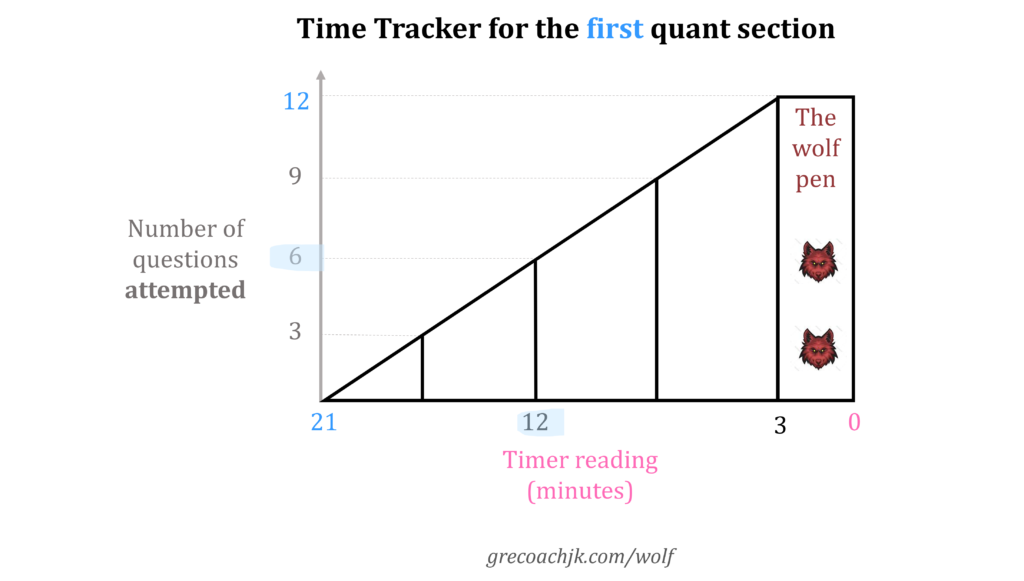

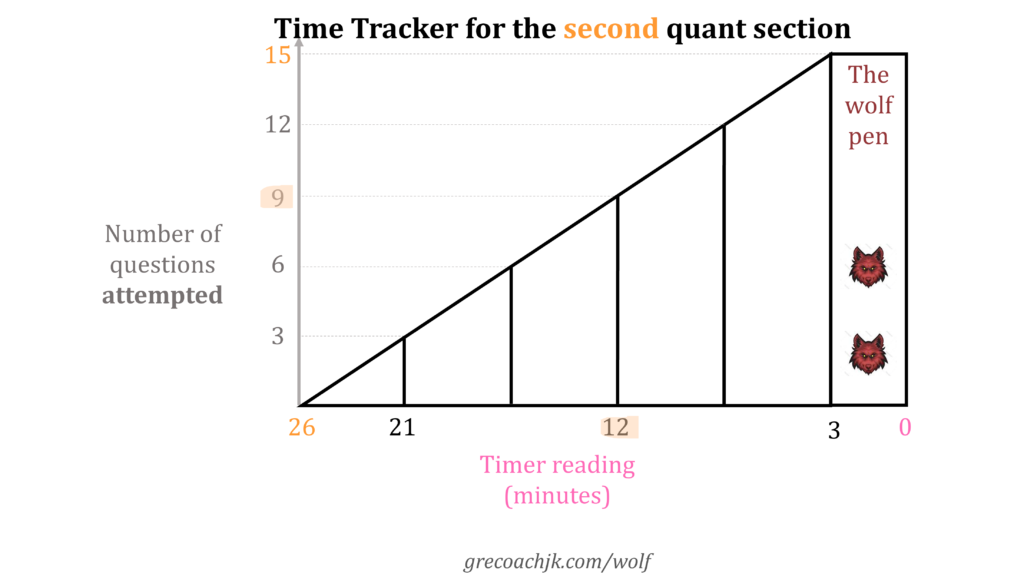

I use the word ‘wolf’ for time-sinking questions, and my name for the rectangle part of the time tracker is ‘wolf pen’. By the end of this article, you’ll understand why.

Jen’s story

Jen (name changed) was a student of mine in November 2022.

[Note: One thing that you should keep in mind when reading Jen’s case study is that at the time she took the GRE, each quant section in the test had 20 questions to be done in 35 minutes (the current, shorter, format of the GRE – there are now only 12 questions in the first quant section and 15 questions in the second quant section – was launched on September 22, 2023).

So, the time tracker that I created to help Jen was accordingly based on the longer format of ’20 questions to be done in 35 minutes.’ The snapshots that you will see later in this article of Jen’s application of this time-tracker map to milestones that were designed for the task of ‘attempting 20 questions in 35 minutes.’ These milestones were different from the milestones suggested in the time-trackers shared above to accomplish the tasks that the present-day GRE sets before you, which are to:

- ‘attempt 12 questions in 21 minutes’, and

- ‘attempt 15 questions in 26 minutes.’ ]

Jen had made two GRE attempts before approaching me, scoring Q161 and Q162 in them respectively. She was frustrated about her tendency to sink inordinate time in some questions during the test due to which some questions at the end of the section got left or had to be rushed through. In her Diagnostic Score Reports (DSRs) for these two attempts, I could see questions on which she had spent 5 or 7 minutes. Particularly egregious had been the time allocation in the second quant section (‘hard’ difficulty level) of her later attempt – she had taken 18 minutes for the first 8 (quantitative comparison) questions and, therefore, had had to anxiously race for the remaining 17 minutes through 12 questions.

One of the initial assignments that I gave to her was around Word Problems, which she had told me was a question-type she struggled in. The task was to do 20 questions in 35 minutes; since almost every question in this assignment involved the reading and understanding of lengthy question statements, I thought it likely that some questions – say, three or four – would remain un-attempted at the 35-minutes mark; after all, ‘20 questions in 35 minutes’ was the time command of the GRE and, unlike my assignment, the GRE does not present you with only word problems.

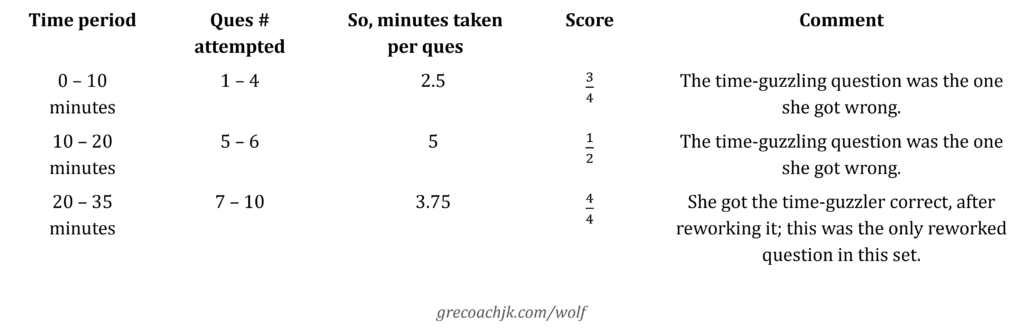

I was startled by how the assignment actually went for her. Jen had helpfully noted timestamps after every few questions; so, we could reconstruct her progress through the assignment, which was as follows:

In the allotted 35 minutes, she had managed to do only 10 questions, of which 8 were correct. Her performance in this assignment had been 8/20, which – considering that the overall difficulty level of my assignment was medium – maps to a dispiriting scaled score of Q148. After the 35 minutes were over, Jen had continued to solve the remaining questions in the assignment under timed conditions. From her timestamps, it was evident that if only she had not sunk so much time on those 3 time-guzzlers among the first ten questions, if she had left them sooner and had managed to reach the end of the assignment within 35 minutes, her score could have been 12/20, which would have mapped to a more respectable Q155. Some of those downstream questions that she could not get to in the allotted time had been quite straightforward and she had solved them confidently in under a minute each.

Jen already knew of her timing problem, but this knowledge had not proved sufficient to solve the problem. Knowledge does not automatically become lived wisdom. An overweight person may know that he needs to create a calorie deficit in his diet and to exercise regularly, and he may want with all his heart to do these things, but his weight problem will still persist if he fails to convert his knowledge and intention into action.

Jen was frustrated with frequently running out of time in quant sections, but at the level of individual questions, in the moment where she had already spent say two minutes on an unruly question, she tended to think that:

- marking it for review now would mean that she would have nothing to show for those two minutes and that she had, therefore, wasted that precious time, whereas

- if she persisted with the question for only a minute more, she may get it right and add 1-point to her raw score.

I thought about how I could reframe the choice between persevering with a question or marking it for review, so that Jen’s focus shifted away from the potential of perseverance to bring a gain of 1-score point to its potential to cause a loss of many much-easier questions later in the section. The bloodbath that the time-guzzling questions had wrought in the word problems assignment made me think of them as evil wolves, reminding me of the fable of the wolf and the sheep. Thus inspired, I created a new take on this story, as presented below.

The wolf in sheep’s clothing

You are a shepherd who has recently bought your first twenty sheep. You pasture them in the day, and after rounding up your flock in the evening, you take them one by one to a feeding post installed in your compound, carefully watching the response of each to the offered food.

The reason for this scrutiny is that you have heard many stories where sheep grazing in open lands were secretly killed by wolves, who then took on the sheep skin and were shut in by careless shepherds with the rest of their flock at day end. After the shepherd went to sleep, the wolves killed and ate most of the herd. You do not want a wolf to enjoy a sheep-feast at your expense.

The wolves in sheep’s clothing do not look very different from the sheep but they do not like to eat plants. So, you keep an eye on the enthusiasm that an animal shows to a trough full of fodder. Those who respond to it with enthusiasm are safely judged to be sheep and are tucked for the night into the sheepfold, while those who show no interest in the greens are locked in a separate enclosure, which you informally call your wolf pen, for closer inspection afterwards.

After this initial sorting, you go to the wolf pen and examine the three animals held there. You find that one was a sheep, which you now move into the sheep pen, while two were wolves, which you kill instantly.

Your caution has paid off. You saved many precious sheep from being slaughtered by those two wolves. You proved to be a good shepherd.

Applying ‘the wolf and the sheep’ metaphor to your GRE quant section

A quant section with twenty questions is like the shepherd’s flock of twenty animals rounded up after a day of grazing. Some of these may be wolves in sheep skin.

Just as the sheep pay back for the shepherd’s care with valuable wool, the sheep-questions pay you back for your effort with valuable score-points; these are the nice, simple questions that you can solve easily. The sheep represent a shepherd’s wealth, and a good shepherd is a fierce guardian of his sheep.

Studying your concepts thoroughly and preparing well for the test is akin to a shepherd being watchful when his sheep are grazing on the pasture so that no wolves can pull them aside and kill them. If he does this job well, he may not encounter a wolf in sheep’s clothing at all; his twenty animals at day end may all be sheep. However, it is also possible that despite all care, some sheep still wanders off into a corner and gets killed by a hiding wolf and, thus, even a diligent shepherd may end up with one or two wolves in disguise within his flock. Likewise, no matter how well you have prepared, you may still get stuck on some questions in the test. Those are the wolf-questions in your flock of twenty.

If at day end, a flock of twenty includes two wolves, that does mean that two valuable sheep were killed by those wolves on the pasture, but well, this loss has already happened and cannot be undone. The shepherd’s task now is to save his remaining sheep from the wolves. To fail to do so is to be a poor shepherd. Here I use the word ‘poor’ deliberately; you can read it either in the sense of ‘bad’ or in the sense of ‘poverty-stricken’, both meanings work: a shepherd who does nothing to save his remaining flock from the menacing wolves is a bad shepherd indeed, and because his wealth is measured by the number of sheep he has, the preventable sheep-slaughter will also make him materially poorer.

In the GRE context, how do you distinguish a sheep-question from a wolf-question? Well, see how it responds to your attention. If it starts to get solved at once, it is a sheep-question, but if it remains indifferent to your effort, it is likely to be a wolf-question.

A question upon reading which an approach towards the solution does not immediately become clear to you is probably a wolf-question; mark it for review (this is like putting a suspected wolf in the wolf pen for closer examination later) and move to the next question. If, on later inspection, a maybe-wolf proves to be a sheep, that’s no harm done; you will still get your 1-point from it. But if you remain unable to solve it, you will feel glad that you didn’t waste too much time on it in your first pass through the section and thus ensured the safety of however many sheep you had.

A poor shepherd is one who forgets the possibility that wolves may be lurking in his flock and makes no effort to identify and separate the wolves. In the GRE, this would be a student who makes no effort to separate the time-guzzling questions from the straightforward and easy questions and engages with both kinds of questions the same way, allowing himself to spend however much time it takes to reach the answer for a question- be it four, five or seven minutes – when there remain many questions that he hasn’t even seen in that section. All the easily doable questions that he fails to attempt in a section because time ran out are the sheep that the wolves managed to kill because the shepherd carelessly shut the wolves in with the sheep for the night.

In your practice sessions, you can count the killed sheep. In the test, you may sadly never come to know!

How much time is too much to spend on one question? The average time available for a GRE quant question is 1.75 minutes, but of course this does not mean that each question should be solved in exactly this much time. Some questions may take only 30 seconds while others may take 3 minutes. How can you decide whether to engage with a question that looks like it may take 3 minutes or to mark it for review and move on? That’s where the time-tracker can help you make a wise choice. For two examples of this, watch from 8:10 onwards ‘the video guide to the Time Tracker’ that is shared at the beginning of this article.

The time-tracker’s impact on Jen’s timing issues

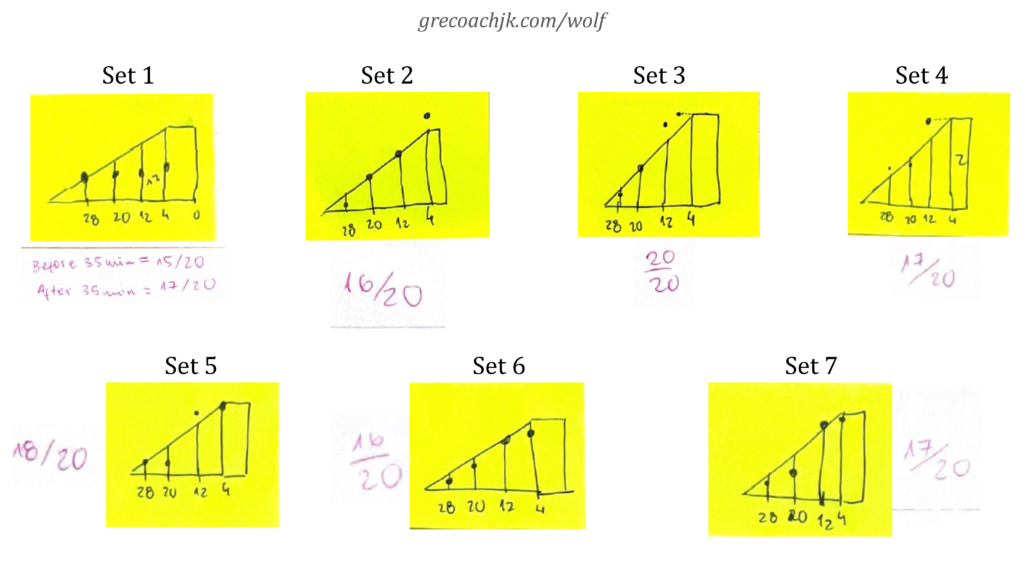

I shared the time-tracker idea with Jen in the discussion session we had around her Word Problems assignment. She said that she’ll implement it for all her forthcoming assignments. There were seven more 20-question assignments that I gave to her, a new one given only after she had submitted her work for the earlier one, and each belonging to a different group of topics. She made her time-trackers on Post-it notes. All seven of them are presented below followed by my interpretive comments for her timing performance.

I should also point out that a person’s accuracy in a question set depends not just on her time management but also on her comfort with the concepts tested in that set and on her attentiveness/fatigue while solving questions.

- Set 1: This was the first assignment for which she made the time-tracker. She was on track at the 28-minutes-left mark but started lagging behind thereafter, by one question at the 20-minutes-left mark, by three questions at the 12-minutes-left mark, and again by three questions at the 4-minutes-left mark. However, the obligation of marking the number of questions attempted at the various milestones did keep her alert and she was quicker in marking questions for review than before.

- Set 2: She started off slow and lagged behind at the 28-minutes-left milestone but then got back on track. The dot above the hypotenuse at the 4-minutes-left mark was her way of noting that she had surpassed the milestone by solving question number 20 before the 4-minutes-left mark. I advised her to denote this achievement instead by moving the dot leftwards, so that its x-coordinate corresponded roughly to the timer-reading at which she was done with her first pass through all questions. She implemented this suggestion in Sets 3 and 4.

- Sets 3 and 4: She faced no timing issues at all and in fact finished the quant section before time.

- Sets 5 and 7: She faced intermittent timing issues, lagging a little behind at some points and then recovering.

- Set 6: She consistently lagged behind, though only slightly, at all milestones. She was still able to make her first pass through all twenty questions but did not have enough time left at the end to reattempt the two questions that she had marked for review.

The total duration for which Jen worked with me was only 12 days. So, the above seven sets were all done within about a week.

She sat for the GRE soon after.

In the first quant section, she made the time-tracker on the whiteboard but accidently erased it quite early in the section; rather than redraw it, she decided to track the milestones just in her head and ended up sinking time on a wolf-question soon afterwards. At the 22-minutes-left mark, she was still doing her sixth question (ideally, she should have attempted around nine questions by then). She then anxiously marked it for review and rushed through the remaining questions with the feeling that she had lost control of the test.

When the second section arrived, the questions felt much simpler than those in the first section. This confirmed to her that she had done so badly in the first section that she had got the easy version of the second section; she despaired of scoring more this time than her earlier official scores of Q161 and Q162. Nevertheless, in this section, she made the time-tracker and had ample time left in the end to solve all the marked for review questions and check her work for some other questions as well. Later, from the Diagnostic Score Report, we discovered that the second section had in fact been of hard difficulty level and that she had scored 15/20 in each section.

Her score in this test was Q161. She told me afterwards that on the morning of the test, the pressure of performance – which we had talked about many times and had tried to tame – had come back and she had worried about how if she did not get at least a Q167 that day, she would not get into any PhD program of her choice, but for this score, she needed to get almost all questions correct and so, she could not afford to not do a wolf-question. And so, she had persevered with that wolf-question in the first section.

This brings me to my last point. Under stress, we revert to our default behaviors; all recently learnt best practices fall by the wayside like an unfastened shawl. Jen had implemented the time-tracker for seven assignments, but this amount of practice proved insufficient to change how she chose under high stakes conditions between engaging with a question and marking it for review. Had she retaken the GRE after this attempt and consistently applied the time-tracker, say, twenty more times, then it is plausible that this time-tracker might have become her new default, something that she did simply as matter of course, no matter how stressed or anxious she was.

*

I hope that you will find the time-tracker to be a pragmatic antidote to your timing woes and also that you will practice it long enough and consistently enough for it to become an ingrained habit with you.

You may also learn from Jen’s experience to not put too much stock in your subjective assessment of the ease or difficulty of questions and of a test section; such meta-analysis is a distraction when all your attention should be focused on the question that is in front of you now.

Jen’s example also illustrates that a super-impressive GRE score may not be as vital to your admission prospects as you fear in your most uneasy moments: she received 5 offers for the PhD, including one from her dream program, which she accepted, and, thus, ended her applications journey on a happy note.

Good luck!