A chalk hit Amar Sharma’s back. Students giggled.

He kept writing on the blackboard. When he was done, he faced the class and asked, “What will be the speed of the train after five seconds?”

No answer.

He made a boy stand up. “Repeat to me what I’ve taught about accelerated motion.”

“I didn’t understand it,” the teenager replied.

“Can anyone tell what equations I discussed today?”

No answer.

This was going all wrong. What would the selection committee think?

Amar had recently graduated from a teachers’ training program. Right now, he was auditioning for the job of a high school physics teacher. This demo class was being recorded.

He had imagined getting a standing ovation from the students. Perhaps the school principal too would gush, “I’ve never seen such a wonderful teacher in my life!”

He wrote in his diary that night.

“Maybe I am not meant to be a teacher. Not a single student understood what I taught. This, despite my having started from the very basics of the concept. I just wanted to walk out of the classroom and the school and never put myself in such an embarrassing situation again. Later, I overheard two members of the committee saying that I had made the lesson needlessly complex and that perhaps I didn’t understand child psychology. This remark stung so bad. They must have thought that I was a fool.

Of course, I did not get selected for this job, but now, I am beginning to think that maybe I cannot be a teacher at all? Especially in schools where the students are as ill-behaved as the ones today. The kids in the teacher training school were so much nicer.

There was I, dreaming of bagging Best Teacher awards. And now see, I cannot even teach. I am ashamed of myself!”

Let’s assume that it is possible to assign objective scores to the performance of teachers. A score of 100 out of 100 indicates flawless performance. This score is rarely achieved and only by expert teachers.

On this scale, let’s say that Amar got a score of 5 in his demo class. His diary entry suggests that he saw this as a failure and couldn’t cope very well.

This was because he was a perfectionist.

In job interviews, when asked to list a personal weakness, many of us answer ‘perfectionism’ because we think that this is a safe answer – something that is not a weakness at all. In calling ourselves perfectionists, we think that we are telling our recruiters that mediocre outputs do not satisfy us, that we set and strive for high standards, and that we have an amazing work ethic.

We are mistaken.

Perfectionism is not equal to striving for lofty standards. It has other, non-pretty features.

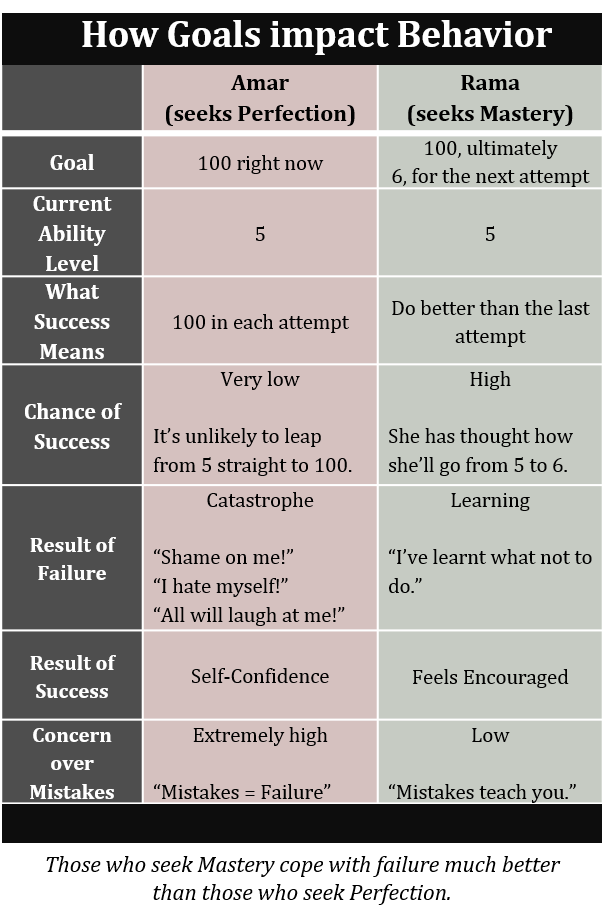

Amar Sharma wanted a score of 100 on his very first attempt at teaching. He wanted a standing ovation. This is the first feature of perfectionism. A perfectionist sets an impossibly high goal for himself, something that is far beyond the reach of his current ability.

Second, he defines success very narrowly. Success only means a score of 100 out of 100. Any other score means failure. Scores of 99 or 90 or 80 or 5 – they all mean failure. So, there is no scope to make even one mistake. Since zero mistakes are rare, failure is almost guaranteed.

Third, he magnifies the results of success and failure. When he fails, he doesn’t say, “I failed in these two things in this particular task.” He says, “I am such a despicable loser!” He generalizes the failure to his whole being. He thinks that others will like him only if he is successful (which, by the way, means a score of 100 out of 100). He too likes himself only if he gets a perfect score. His self-acceptance is conditional.

Fourth, he is very concerned about making mistakes. Mistakes mean failure to him. Because the cost of failure is so high for him, he wants to avoid it at all costs. He will rather not do something than risk doing it badly. Or, if he starts doing it, he will try to postpone judgment. If his performance does get to the judgment stage and the judgment is not favorable, he will try to convince others and himself that it was not his fault. That if all had gone well, he would have scored 100 out of 100. In his mind, only flawlessness is worthy of respect and admiration.

Thus, perfectionism goes far beyond mere pursuit of excellence. It is, in fact, a path to personal hell. First a perfectionist sets himself an unrealistic goal. Then, he promises to flagellate himself if that goal is not reached. Then, knowing that he may not in fact reach the goal, he desperately tries to avoid that flagellation.

It is a distorted, tragic way of working.

To help you better appreciate how unhealthy perfectionism is, let’s consider Rama Sharma.

Rama Sharma too is a novice teacher. She too taught the same demo class and had the same experience as Amar. She too got a score of 5.

Like Amar, she aims to get a score of 100 out of 100. There is one difference though: while Amar seeks perfection, Rama seeks mastery. The perfect score of 100 is Rama’s ultimate goal. She knows that mastery is a long way off. To earn a perfect score, she first needs to put in a lot of practice.

Here is what Rama wrote in her diary after the demo class:

“I did not get the job. That was to be expected after I did so bad in the demo. When I came out of the classroom, I was feeling low. But then, I reminded myself that mistakes help you learn! I sat down at the nearest spot I could find and wrote some top-of-the-mind ideas about what I could do better the next time. This helped me feel confident again.

Then, I thought to try my luck and seek feedback from the selection committee.

I’m glad I tried this. A senior teacher in the committee agreed to my request. She was very nice and encouraging. “Teaching is a complex job,” she said; “it is normal for a new teacher to struggle.” She suggested that to begin with, I should work on two skills:

- Friendliness – today, I seemed too strict and formal with the students.

- Lesson planning – I stuffed too much into one lecture. Also, my examples were too abstract for the kids.

My goal for the next interview is to implement this tip and the ideas I thought myself. I scored a 5 today. I should try to get a 6 the next time.”

Rama coped with a low score much better than Amar.

In the next interview, who do you think is going to do better?

After five years, who is more likely to be the better teacher?

Many research studies have linked perfectionism with poor performance. Others have linked it with stress, depression and even a higher rate of suicide.

A perfectionist demands perfection here and now. He sets impossibly high goals. Quite like a five-year old who climbs trees well and decides that he may be considered a good climber only if he can summit Mount Everest today. It’s all or nothing. By defining success so narrowly, he sets himself up for failure, and he attaches such high costs to failure that it starts to seem like a catastrophe whose slightest mention fills him with anxiety.

Failure is an integral part of learning and getting better. In trying to avoid failure, a perfectionist ends up avoiding mind-stretching projects that are beyond his capacity at the beginning and, thus, severely hampers his growth and performance.

It is much kinder to oneself to aim at mastery. Like Rama, one should set realistic goals and look at mistakes as learning opportunities.

A child who climbs trees practices to get better, one skill at a time. He keeps at it for years. This is how he becomes the man who climbs Mount Everest.

References

1. The resource that I turned to the most in writing this article was the essay ‘Perfectionism: A Foundation for Sporting Excellence or an Uneasy Path Toward Purgatory?’ by Hall, Hill and Appleton. This essay is a meta-analysis of the research done till date on the effects of perfectionism in sportspersons. However, since the research done on perfectionism in sports is rather limited, the essay often references general research on perfectionism. So, it provided me a good overview of the existing academic literature in this field.

2. The case studies of Amar and Rama Sharma are fictionalized. They are however inspired from the research paper published by Drs. Helen Demetriou and Elaine Wilson of the University of Cambridge: It’s bad to be too good: the perils of striving for perfection in teaching

Written by Japinder Kaur; also published on LinkedIn.