Scheherazade and the Micro-Accountability Contract

“If you will allow me, father, I will marry the king,” Scheherazade said.

“Are you out of your mind?” her father asked. “This is suicide! There is no way I’ll let you marry that brute.”

There was a time when king Shahryar had been well-loved by his subjects. Then, one day, he had found that his beloved wife was cheating on him with a slave. He put them both to death and decided that all women were untrustworthy. To never get cheated on again, he started marrying a new girl every day and hanging her the next morning. This had been going on for years.

Scheherazade’s father was Shahryar’s wazir. It was his job to find suitable brides for the king. That day, he could not find any. The last eligible girl was hanged that morning.

He was afraid of the king’s wrath if he showed up empty-handed. Seeing him worried, Scheherazade had made this absurd suggestion.

“There is a reason why I want to do this, father,” she said. “I have a plan.”

After a lot of persuasion, her father relented.

The king married Scheherazade and they spent time together in his chamber. When the king was about to sleep, she made a request.

“Dear King, I’m going to die in a few hours. If you don’t mind, can I spend these remaining hours with my loving younger sister? I’ll call her here and we’ll talk while you sleep.”

This was a harmless idea. The king gave his permission.

Her sister came in and, as per the plan, soon asked Scheherazade to tell her a story. Scheherazade began to tell one.

The king was still awake. He too started listening.

The story had just become very interesting when dawn broke. Hangmen came to fetch Scheherazade. The king told them to come the next day. He wanted to know how the story went on.

That night, Scheherazade finished the story. Since it was still midnight, her sister requested her to tell one more.

Again, this second story was at its peak when the hour of death came. Again, the king was unable to stand the suspense of what happened next in the story. He put off the queen’s death by another day.

This went on for a thousand and one nights. The collection of these stories is known as The Arabian Nights. By the last story, the king was convinced that Scheherazade was no ordinary woman. He waved off the death sentence. And, they lived happily ever after.

So the story ends well. But why did Scheherazade take such risk in the first place?

I have a theory. I think that before her marriage, she was a writer who struggled with procrastination. She was always wanting to write but hardly ever actually wrote, because some more immediate or urgent things were always coming up to command her attention. That day, when she saw her father worried, she got an idea. Marrying the king would put her in a do-or-die situation. If she didn’t now come up with a new story every day, she would die. And the strategy paid off!

An arrangement like the one Scheherazade entered into can be called a Micro-Accountability Contract. Making such a contract is a great way to get an important task done. If you have been wanting to take the GRE, have been sort-of-preparing for the test for a long-time now but never reached the point where you felt confident enough of doing well in the test, then read on. The solution to your problem may be to make a Micro-Accountability Contract.

The General Recipe for Micro-Accountability Contracts

Here is the four-step recipe to make such a contract:

- Break down your big goal into smaller (micro), realistic deliverables. For example, Scheherazade broke her dream of writing hundreds of stories down to a doable goal of writing one new story each day.

- Make each deliverable binding. You should not be able to change the deadline or the terms and conditions later. For example, Scheherazade knew that if she failed to write a new story, she would be hanged the next morning. The king would not have mercy on her.

- Make each deliverable measurable; there should be no ambiguity about whether the deliverable was achieved or not. For example, Scheherazade only needed to write one story per day.

- Set a high cost to not achieving the deliverable. For Scheherazade, the cost was her life.

Scientific Proof that Micro-Accountability Contracts Work

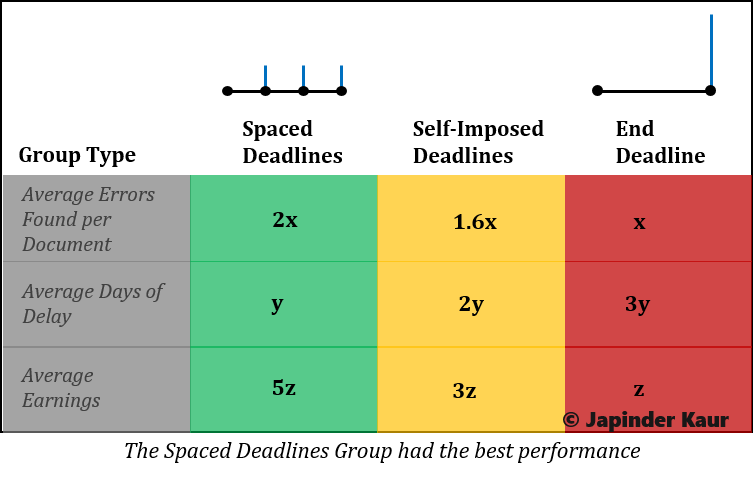

A study done by Professor Dan Ariely on MIT students shows the power of Micro-Accountability Contracts. All participants were asked to proofread 3 documents in 21 days. Each document was 10 pages long, difficult to read and had exactly 100 grammatical errors. The participants were divided into 3 groups:

- The Spaced Deadlines Group – The research team told these students to submit one proofread document every seven days.

- The End Deadline Group – These students were told to submit the three documents together at the end of 21 days.

- The Self-Imposed Deadlines Group – These students were asked to choose submission dates, within the 21-day period, for each of the three documents. Once chosen, the deadlines would be binding.

The students would earn 10 cents for each correctly detected error. (So a student could earn a maximum of $0.10*100 = $10 per document).

The conditions in the Spaced Deadlines group had all the features of a Micro-Accountability Contract:

- The big goal of proofreading 3 long and difficult documents was broken down into 3 smaller deliverables. Since the documents were similar in their difficulty and number of errors, it was realistic to give the same number of days for each document.

- Each deliverable was binding. The research team accepted no excuses for delay.

- A deliverable meant exactly one proofread document. So, each deliverable was finite and measurable.

- There was a fine of one dollar per each day of delay.

On the other hand, the conditions in the End Deadline group were similar to how your test-prep situation has probably looked like till now: there is only one big deadline – the Test Day – and no sub-deadline, no micro deliverable before that. And even this one big deadline is not externally imposed (well, not entirely; it’s externally imposed only to the extent of the application-submission deadlines of your target schools), and I know people who have kept pushing it from one year to the next. They are always meaning to take the GRE but never actually take it.

The research team found that the Spaced Deadlines group did far better than the End Deadline group. They detected many more errors, had much lesser delay and so, earned more.

The study also highlighted the importance of setting realistic deadlines for these deliverables. The team noticed that in the Self-Imposed Deadlines group, students who gave themselves equal time for each of the three documents performed as well as the Spaced Deadlines Group. However, the students who gave themselves more time for one document and therefore lesser for the other documents did not do as well (and brought down the performance of the group as a whole). This too is an important point. It indicates that not everyone is equally adept at setting realistic deadlines. When asked to divide the whole Quant syllabus into smaller modules and fix study-deadlines per module, there could be students who assign too much time to a smaller module, thereby leaving less time for a bigger, later module. This sub-optimal allocation of time across the modules, if one extrapolates the results of Professor Ariely’s research to test-prep, would impair the performance of these students, but this performance would still be better than that of the students who set no smaller deadlines for themselves at all.

Why Micro-Accountability Contracts Work

One reason why you might be struggling to study regularly for the GRE could be that the rewards of taking the test and scoring well in it, or the costs of not taking it are far out in the future. Standing where you are today, these rewards and costs probably appear tiny. On the other hand, the rewards of answering an email or surfing the internet or watching something on Netflix or attending a social function right now are very much real. So, you might end up doing the thing that will give you a small but immediate reward instead of the thing that will give you a bigger but later reward.

A Micro-Accountability Contract brings that far-away cost or reward into your present.

Another Example – David Stops Procrastinating

The book Nudge tells an anecdote about how the book’s coauthor and the Nobel-laureate Professor Richard Thaler made a young colleague named David sign a Micro-Accountability Contract.

David had been hired as a new faculty member before he finished his Ph.D. He needed to finish his Ph.D. thesis latest by the end of his first year at the job.

David procrastinated on the thesis. In comparison to the exciting projects that he was a part of at the university, writing the thesis seemed dull and boring. He was alarmingly behind his planned schedule for the thesis when he discussed the matter with Professor Thaler.

Professor Thaler took a number of checks of $100 from him, each payable on the first date of one of the next few months.

“I need a new chapter of your thesis by 12 AM on the first day of each month,” he told David. “If I don’t get it, I’ll cash the check for that month and have a party with that money and, by the way, you won’t be invited to that party.”

David knew that this was not an empty threat. Professor Thaler would actually cash the check.

Four months later, David was done with his thesis. He had not missed a single deadline. The fear of not just losing the money but also his face before a senior colleague kept him submitting all deliverables on time.

Applying this to your Test-Prep

In your school and college, your teachers have imposed Micro-Accountability Contracts on you (homework assignments, regular tests, final exams etc.). At work, your boss imposes such contracts (“I want this report by Friday, or else…”). These authority-figures let you know what you need to deliver, by when, and what would be the costs of not meeting the deadline.

Does anyone play that role in your GRE prep? If not and you are not happy with how your prep has been going on till now, then you may need to design your own Micro-Accountability Contract, like Scheherazade did. Here’s how you can do it:

- Break down the Verbal and Quant syllabus into smaller goals. Set realistic deadlines for each. For example, you may set yourself the goal of doing Statistics by this Sunday.

- Set in place a system that punishes you for not meeting these deliverables. This punishment must be inescapable. The matter should be as simple as, “You did not do all that you had promised to by Sunday, so now suffer.” There should be no scope of melting the heart of your task-master (your own Professor Richard Thaler or King Shahryar) due to this excuse or that ameliorating circumstance. Look into your life for someone who can hold you accountable. Perhaps a strict elder sibling, or a best-friend who doesn’t mind scolding you when needed, or a disciplinarian uncle?

- Make each study-deliverable measurable. For example, if your deliverable is ‘doing Statistics by this Sunday,’ you should clearly define what the ambiguous word ‘doing’ means – what all topics will you be covering (perhaps mapping these topics to specific page numbers in the Official Guide Math Review section), Official Guide questions on this topic, revision of your mistakes on these questions etc. Your task-master should, at the very least, expect from you, on the due date, a summary report of the status of each to-do; it would be even better if he or she can test you on that topic.

- Set a high cost to not achieving the deliverable. For Scheherazade, the cost was her life. If your task-master is a family member or a friend, the cost is shame (quite high a cost for sensitive and self-respecting people).

Should you find no one who will be as strict a task-master for you as you need, or should you still keep getting overwhelmed by the bigness of the whole GRE Prep and struggling to keep your focus on just doing “Statistics by this Sunday,” you could look for a good private tutor. A private tutor not only helps with clearing subject-matter related difficulties during your GRE prep, but also, should you ask her to organize your test-prep, breaks down the seemingly huge and amorphous syllabus into smaller, manageable chunks, helps you set realistic deadlines for each chunk, and holds you accountable for each deadline.

Devising a Micro-Accountability Contract took Scheherazade from a struggling writer to the proud creator of one-thousand-and-one stories, and David from a novice academic in risk of losing his job due to the non-completion of his PhD thesis to someone who completed that thesis with a flourish. It could also take you from someone who had been feeling overpowered by GRE to one who prepares for the test with style and gets a great score at the end. Good luck!

Written by Japinder Kaur; also published on LinkedIn.

A related article

How to balance GRE prep with job? Anthony Trollope may help you.

Reference Notes

- You can read Professor Dan Ariely’s research paper here. Description of the study described in this article starts on page 4.